Artículos

Mothers’s Parenting Styles, Academic Self-Efficay and Academic Performance: Chinese-Spanish Cross Cultural Study

Estilos de crianza de las madres, autoeficacia académica y desempeño académico: Estudio transcultural China-España

Mothers’s Parenting Styles, Academic Self-Efficay and Academic Performance: Chinese-Spanish Cross Cultural Study

Ehquidad: La Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, núm. 22, pp. 215-254, 2024

Asociación Internacional de Ciencias Sociales y Trabajo Social

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 23 Marzo 2024

Revisado: 26 Marzo 2024

Aprobación: 27 Marzo 2024

Publicación: 26 Abril 2024

Abstract: Abstract: This study aims at investigating and highlighting the diversity in mothers' parenting style and self-esteem and their correlations with academic achievements across cultural contexts. A total of 200 university students (100 from China and 100 from Spain) was taken by means of the purposive sampling method. During the course of the 2021-2022 Academic Year, the Parenting Style Scale (S-EMBU) and Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES) were used to assess mothers' parenting styles and self-efficacy. It was found out that there were several cultural differences in the way parents approach their children, with the Spanish mothers applying warm and affectionate attitudes and the Chinese parents using stricter methods. As for the difference, no statistical significance was found between the two groups related to academic self-efficacy. In the findings, the rejection type of parenting was associated negatively with self-efficacy and academic performance while warm parenting that is emotional in nature was positively associated with these outcomes among university students. Furthermore, a positive connection between academic self-efficacy and academic success is also observed. The research identified specific parenting behaviors of mothers that significantly affect students’ academic performance in university, which reveals the critical role of parents in student’s academic success. Generally, the study shows the significance of cultural variation in parental involvements into university students' academic performance and the key role of parenting in the students' academic success. The research also considered parenting styles and academic self-conceptualizations between the Chinese and the Spanish university students. While it is true that there were notable cultural differences in parenting styles between Spanish mothers who showed warmer and more expressive styles and Chinese mothers, there were no significant differences in subjects’ self-efficacy in learning processes between the two groups. These results emphasize the significant role of parenting in the predictability of academic achievements among university students. In this sense, parental styles that involve emotional warmth were found to correlate with higher levels of academic self-efficacy and better academic performance. The research shows that positive ways of parenting including fostering emotional closeness and caring could help improve children's school performance.

Keywords: Mothers, Parenting styles, Academic self-efficacy, Academic performance, EMBU.

Resumen: Resumen: Este estudio pretende investigar y poner de manifiesto la diversidad en el estilo de crianza y la autoestima de las madres y sus correlaciones con los logros académicos en distintos contextos culturales. La investigación se realizó durante el curso 2021-2022. Para la muestra, se escogió un total de 200 estudiantes universitarios (100 de China y 100 de España) mediante el método de muestreo intencional. Se pasaron la Escala de Estilos de Crianza (S-EMBU) y la Escala de Autoeficacia Académica (ASES) para evaluar los estilos de crianza y la autoeficacia de las madres. Se descubrió que existían varias diferencias culturales en la forma en que las madres se dirigen a sus hijos, mostrando las madres españolas actitudes cálidas y afectuosas y aplicando las madres chinas métodos más estrictos. En cuanto a las diferencias, no se encontró significación estadística entre los dos grupos en relación con la autoeficacia académica. El estilo de crianza llamado “rechazo” se asoció negativamente con la autoeficacia y el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes universitarios, mientras que la crianza cálida y de naturaleza afectiva se asoció positivamente. Además, también se observó una conexión positiva entre la autoeficacia académica y el éxito académico. La investigación identificó comportamientos parentales específicos de las madres que afectan significativamente al rendimiento académico de los estudiantes en la universidad, lo que revela el papel fundamental de la familia en el éxito académico de los estudiantes. En general, el estudio muestra la importancia de la variación cultural en la implicación de las madres en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes universitarios y el papel clave de la crianza de los hijos en el éxito académico de los estudiantes. La investigación también examinó los estilos de crianza y las autoconceptualizaciones académicas entre los estudiantes universitarios chinos y españoles. Si bien es cierto que existían notables diferencias culturales en los estilos de crianza entre las madres españolas, que mostraban estilos más cálidos y expresivos, y las madres chinas, no había diferencias significativas en la autoeficacia de los sujetos en los procesos de aprendizaje entre ambos grupos. Estos resultados enfatizan el papel significativo de la crianza en la predictibilidad de los logros académicos entre los estudiantes universitarios. En este sentido, se observó que los estilos parentales que implican calidez emocional se correlacionan con mayores niveles de autoeficacia académica y mejor rendimiento académico. La investigación muestra que las formas positivas de crianza que incluyen el fomento de la cercanía emocional y el cariño podrían contribuir a mejorar el rendimiento escolar de los niños.

Palabras clave: Madres, Estilos de crianza, Autoeficacia académica, Rendimiento académico.

1. INTRODUCTION

Exams is the primary means of precisely measure the learning progress in a semester or a school year, and exam preparation can motivate students to be more active in education (Wang, 2022). After the examination, students can recognize the gaps in knowledge, which can help teachers and students identify areas that need additional improvement and improvement (Tremblay, 2012, pp. 190-192). The academic examination is a learning assessment for university students (Liu & Chen, 2020). However, from the analysis of the scale higher learning is developing to expand, the problematic of the problems is similar all over universities, that have not been seen in elite education, such as "terrible academic performance" among university students. This problem presents a "surprising" situation regarding quantity and its characteristics (Li, 2020; Sandoval-Palis et al., 2020; Yao, 2017; Yuan, 2022). For example, in the US, the rate of academic failure is around 15 percent, compared with approximately 24 percent in member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In contrast, the incidence of academic failure among Columbia college students is about 53% (Sandoval-Palis et al., 2020). Among them, many factors affect academic performance, of which the most important ones are learning self-efficacy (Zhao & Cao, 2023) and family upbringing style (Yuan, 2022; Yuan et al., 2022).

To approach this question, the paper first part analyzes the family parental. Parenting style as a kind of ability upbringing has been revealed to be correlated with self-efficacy, which can predict and affect college students' interpersonal communication, personal development, career development, and mental health (Aldhafri et al., 2020; Liu & Chen, 2020; Turner et al., 2022; Zhao, 2017; Zhang & Kong, 2019). Especially the mothers' parenting style (Keller et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2015). Therefore, it is apparent that the role of the mother is essential in the development of a person's life, and this study also includes the mothers' parenting style as one of these aspects.

The second part highlights the self-efficacy. According to Bandura's social learning theory, the influence of self-efficacy on behavior is mainly manifested in behavior choice, effort level and persistence, coping style, and emotional response (Bandura, 1986; Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). Self-efficacy should be linked to specific events, so the self-efficacy related to "learning" can be called academic self-efficacy. The cognition of academic self-efficacy is affected by various factors, and parenting style is one of the main influencing factors. According to the literature review, though, studies have shown that students' academic self-efficacy not only directly affects their academic performance but it is also a cornerstone and indicator of one's lifetime achievement (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016). Theoretical self-efficacy beliefs affect students' educational levels and career choices and can effectively encourage students to improve their academic level (Greco et al., 2022). However, based on two cultures (China and Spain), there needs to be related research on the relationship between parenting style (mother), academic self-efficacy, and achievement. Its findings on all three could be more varied and consistent. Therefore, this study will summarize and integrate these results, take college students (aged 18-24) as the research objects, and try to put forward a reasonable theory describing the three aspects of a mothers' parenting style, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement.

The comparative analysis of parenting styles and academic self-efficacy between Chinese and Spanish cultural milieus demonstrates the extent to, which culture influences educational achievements. Shengyao et al. (2024) state that Confucian values in China have substantially affected the social order and practices, including education and parenting. Followed by Confucius' advice to be diligent, respectful and filial, authoritative parenting styles prevail. Chinese parents are always keen on academic success, which for them equates to future fulfillment. This cultural expectation can cause a high level of academic self-efficacy among students, as they always have high academic standards set for them. However, this stress also may result in stress or anxiety which may affect students' emotional health and their overall perception of academic achievement. Ortiz (2020) confirms that the Spanish culture, built on “personalismo” (the value of personal relationship) and “familismo” (family ties), may offer a more balanced outlook on education and parenting. Spanish parents are prone to authoritative-supportive style, combining warmth and supervision with demands of autonomy and independence. This method can foster students’ sense of self-efficacy by instilling in them a feeling of independence and self-management and encouraging them to believe in their capacity to successfully complete their academics on their own by applying various strategies. In contrast, the less demanding academic sides in Western culture may result in the differences in academic self-efficacy levels and that may affect academic performance in different ways.

The interactions of parenting styles with academic efficacy among these cultural contexts reflect the wide range of cultural educational psychology. In China, the high standards and the planned approach may create a strong feeling as students achieve various structured academic tasks, and eventually help them build strong success strategies. On the other hand, a similar stress might reduce students' understanding of how much they can achieve in a less confined environment. In Spain there could be more confidence and autonomy that would allow students to deal with the challenges of academic life as well as other domains, so they would develop a more complete sense of self-efficacy (Jinping, 2017).

It is through this comparative analysis that the subtle mechanisms of culture that underpin the linkage between parenting styles and academic self-efficacy are made apparent. However, the level of self-efficacy demonstrated by the Chinese students in the face of particular academic challenges may differ from the situation encountered by Spanish students, for whom a more general and adaptable sense of self-efficacy might be more beneficial in dealing with various kinds of problems (Nguyen et al., 2018). Knowing the unique cultural attitudes and practices is essential for teachers and officials when they want to make educational programs and help systems that are culturally relevant and relevant to the different educational needs of the students.

Considering the two cultural contexts, Chinese and the Spanish culture, it becomes apparent that multiple factors would contribute to the way parents influence academic self-efficacy which in turn affect the academic performance of their children. Hence, Chen (2016) stipulated that in the Chinese case, the authoritarian parenting style, which is associated with high parents' expectations and strict punishment, commonly lays the foundation for a competitive educational environment. Students are thus prone to cultivate loyalty and strength of character which are traits that are very likely to help in inducing academic self-efficacy (Chen et al., 2000).

On the other hand, this passionate devotion to educational accomplishments may also diminish the definition of success, thus stifling creativity and hindering the exploration of interests that do not relate to academics directly (Chen et al., 2015). However, another study carried out by Xiao et al. (2021) found that although Spanish parenting prefers more authority-supportive style and encourages individualism and self-reliance, that way of parenting will help children explore their interests widely and develop a well-rounded personality. This kind of development is going to play a positive part in students' self-efficacy, aside from just academics, but in real life too. With such an approach, it could create flexible learners who are assured to tackle different problems, nevertheless, such approach could also lower down the average academic drive as opposed to their Chinese counterparts.

Based on those, and through a literature review in Chinese and English, this paper will define the research objectives of this study.

-

To compare and analyze the correlation between mothers' parenting styles and the self-efficacy of university students from China and Spain.

-

To investigate the relationship between mothers' parenting styles, their children's self-efficacy, and academic performance within these distinct cultural contexts.

-

To assess the predictive power of mothers' parenting styles on students' academic self-efficacy and achievement.

-

How do mothers' parenting styles and their correlation with academic self-efficacy differ between university students from China and Spain?

-

What is the nature of the relationship between mothers' parenting styles, university students' self-efficacy, and their academic performance in China and Spain?

-

Can mothers' parenting styles predict the academic self-efficacy and achievement of university students, and if so, how does this predictive relationship vary between China and Spain?

2. THE ROLE OF FAMILY IN MULTICULTURAL INTEGRATION AND COMBATING RACISM

The significance of the "family" in education, emphasizing its role as a foundational institution for sustainable human society development (Getswicki, 2016; Julian, 2013). Parents, deemed the most crucial members of the family, bear the responsibility of nurturing their children through family education, a process that involves teaching, socializing, and providing for the child within the family unit (Machowska-Kosciak, 2020). This form of education is foundational, laying the groundwork for future learning and success. In the context of today's globalized society, families also play a vital role in combating racism and xenophobia, particularly among Spanish families, by acting as intercultural mediators (Llevot & Bernad, 2019, 2021).

Parents are encouraged to teach their children to respect diverse cultures, engage in various cultural activities, and participate in volunteer work, fostering integration into multicultural communities. The collaboration between families and schools enhances the effectiveness and longevity of these efforts, underscoring the importance of a consistent and supportive approach in multicultural integration and the prevention of racism and xenophobia (Andrés-Cabello, 2023; Llevot & Garreta, 2024). The review concludes by asserting that this is an ongoing process, extending throughout an individual's life, with family members playing a crucial role in shaping a child's development.

2.1. Parental style

The concept of "family upbringing" encompasses both restrictive and liberal interpretations. Restrictively, it refers to education among family members, primarily from parents to children (Van Voorhis et al., 2013). Parental style, a response to children's behavior during education, is considered a stable pattern formed during child-rearing (Cheah et al. 2009; Chen, 2016; García et al., 2018). It is seen as a blend of concepts, emotions, and behaviors, believed to be profound in shaping children (Doepke & Zilibotti, 2017). However, some authors (Baidi, 2019; Sahithya & Vijaya Raman, 2021) argue that parental style reflects parents' personality attitudes and should be viewed as a behavioral tendency in education. Contrarily, Judith Harris (2011) and Benish-Weisman (2022) challenge this, suggesting peers have a more significant impact on children's development than parents. For this paper, parenting style is defined as a collection of behaviors and emotions adopted by parents to educate, analyzed through Chinese-Spanish family education concepts, educational behavior, parenting styles, and their measurements.

Since parenting style is a complicated mixture of behaviors, feelings and attitudes, the paper comes up with the ways through which culture blends with them. In the case of Chinese and Spanish families, parental style is characterized by certain behaviors, which are influenced by the cultural values, the social norms, and the historical events. In the tradition of the Chinese culture, the key concepts of the philosophy of Confucius deal with compliance with authority, the accomplishment of which leads to communal harmony and educational excellence, which in turn result in a more authoritative and achievement-oriented parenting style as mentioned by García et al. (2018). This mechanism denotes that a parent should be acting as a leader or enlightening a child for success using a more holistic idea. On the contrary, the Spanish family education is based on an individualistic cultural ethic that cherishes personal freedom, family bonds and authority between parents and children. (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Pasquarella et al., 2015). In this way, the parenting style might be classified under the permissive or authoritative-supportive type, orienting children to discover their interests and make decisions on their own, while, at the same time, providing the family with support and guidance.

2.2. Parental styles definition

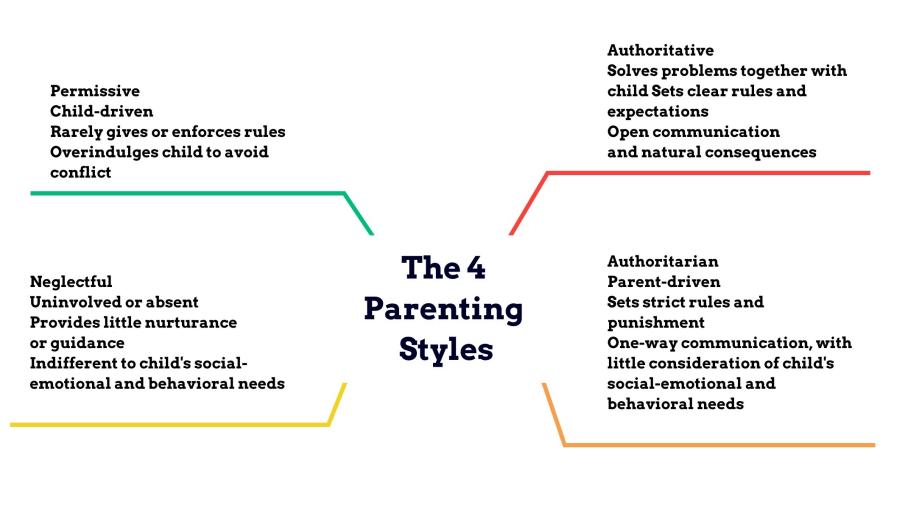

In the 1970s, American psychologist Baumrind studied parenting, integrating two parameters: parental demands and responsiveness, highlighting that parenting behaviors interconnect to form various styles. She categorized these into permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative styles (Baumrind, 1971, 1991). Expanding on this, a fourth style, Neglectful Parenting, was introduced by Maccoby & Martin (1983). Many experts and organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, endorse Baumrind’s authoritative style, advising parents to adopt it. Notably, the widely sold book "Parenting with Love and Logic" by Foster Cline and Charles Fay (2020) is rooted in Baumrind’s parenting styles.

Figure 1.

The 4 Parenting Styles

Source: Own elaboration from Baumrind (1971).

Figure 1 outlines four parenting styles. Authoritarian parents adopt a democratic approach, valuing their child's input and fostering independence, often using logical explanations to guide them. Permissive parents tend to solve their child's problems for them or encourage seeking help, rarely letting them handle challenges independently. Caring parents usually make decisions for their children, aiming to shield them from life's difficulties but potentially stifling their ability to navigate challenges independently. Neglectful parents maintain a hands-off approach, fostering independence but lacking in guidance, which can lead children to develop a negative life outlook and potentially engage in delinquency.

While Baumrind's parenting styles are commonly depicted as distinct categories, parents may actually employ various styles depending on the situation or child, highlighting the complexity of parenting behavior. Additionally, research on Baumrind's styles has yielded inconsistent findings, with some studies suggesting that permissive parenting can lead to positive outcomes in specific cultures or contexts, challenging Baumrind's general association of this style with negative outcomes.

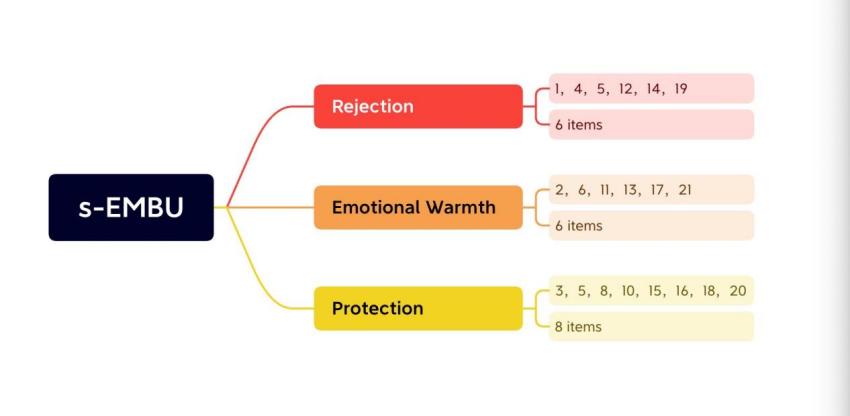

EMBU which stands for "Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran" (My memories of upbringing) is a questionnaire built by the Swedish psychologists in 1980 with the aim of assessing specific parenting behaviors and experiences, such as emotional warmth, overprotection and rejection. This tool requires the person, who is usually an elderly adult, to look back on their parents' parenting style, resulting in its wide use in this field (Aluja et al., 2006; Perris et al., 1980) The questionnaire consists of 81 items and take up to 162 responses for both parents that is quite exhaustive. It is extensive but it is also acceptable by almost all cultures and languages (Arrindell et al., 1999). This demonstrates its efficiency and credibility. In China, most scholars have reached a consensus to use the Parenting Styles Scale (EMBU) modified by Yue et al. (1993). Forever, the study conducted in China by Sijia & Yaoujun (2023), based on the China Education Panel Survey, examines the parental socio-cultural and political effects on parenting practices, they constructed a new typology of parenting styles – intensive, permissive, authoritarian and neglectful.

Besides the obvious limitations of long tests such as the original 81-item EMBU for the measurement of perceived parental rearing behavior, an abbreviated form, s-EMBU, was devised in order to tackle this problem (Arrindell et al., 1999). This short form consists of three scales: love, comfort, feelings of warmth and protection, and a total of 23 items. Its validity and reliability was confirmed in a study involving 2373 students from Italy, Hungary, Guatemala and Greece, making s-EMBU a functional equivalent to the long version. Arrindell et al. (2005) conducted another research and validated a short version of the EMBU, s-EMBU, which has three subscales. It has been proven as a highly reliable, valid, and easy to administer across a variety of cultures. The study covered 1590 students from Australia, Spain, and Venezuela. Hence, the s-EMBU has proven to be a valid and effective measuring tool for future work.

Thus, this research aims to gather data from a diverse group of Chinese and Spanish university students, utilizing the s-EMBU to focus on children's subjectivity and competence development, contrasting Baumrind's parenting styles that emphasize parental behavior and attitudes. While Baumrind highlights authoritative parenting as most effective, the s-EMBU encourages fostering children's abilities, promoting self-reliance, and self-management (Arrindell et al., 1999; Perris et al., 1980), reminding parents to support their children's development. To align with the study's objectives and control variables, the questions were adapted to the s-EMBU, ensuring brevity and relevance based on previous psychometric analyses, and omitting questions to control for peer variables like the influence of siblings. Figure 2 provides details on the s-EMBU scale selection, with a reliability test shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

S-EMBU

Source: Own elaboration from Arrindell et al. (1999) and Perris et al. (1980).

2.3. Research status of differences in mothers' parenting styles under different cultural backgrounds

Since the late 19th century, Freud and others have recognized the impact of distinct parental roles on children, with mothers providing warmth and fathers enforcing rules. This idea was later expanded by Parsons, linking parenting styles to gender roles. Froebel emphasized the crucial role of mothers in shaping society. Since Baumrind introduced parenting styles in 1971, Western research has consistently found authoritative parenting to be most beneficial for children's academic performance. However, studies comparing Chinese and Western cultures have shown mixed results, with some finding a positive correlation between authoritative parenting in Asia and children's self-regulation, while others argue that parental influence is not a reliable predictor of academic success. This study aims to explore how mothers' parenting styles in Spain and China influence college students' academic performance, considering the different cultural backgrounds (Young et al., 2021).

It is the Spanish individualism, warmth, and freedom that serve as the factors which facilitate the parenting style that involves family talks, nurturing, and independence. This fits with the authoritarian style which research has found to be the most effective in the Western culture as well. A Spanish sociocultural background that places family ties and work-life balance at the center also contributes to the generation of students who are self-directed and motivated and have academic competencies (Garcia & Gracia, 2009; García et al., 2018). Then, the culture of China works as an illustration of the role of Confucian values such as respect for authority, collectivism and educational achievements in the society. Over there, an autocratic leadership charged with a high-demand structure where tight control and discipline prevail is a common trend. In spite of the fact that it does not directly affect the Western view of authoritarianism as harmful, however. Chinese families may still show their affection in this way, but in the midst of guidelines of strictness and high threshold (Herrmann-Pillath, 2016). These cultural subtleties imply that the effect of parenting styles on academic achievement may not be generally valid but it has to be disclosed in specific cultural backgrounds.

In the case of Spain where the personal independence is considered as one of the main cultural values, as well as, the social cohesion and emotional intelligence, there is a tendency to adopt an authoritative-supportive parenting style. Thus, such approach creates a milieu, where children are encouraged to be autonomous, self-reliant and emotionally responsive, characteristics which are believed to have a link to academic motivation and self-efficacy (Errasti Pérez et al., 2018). The Spanish model underlines the role of the parental warmth, open communication and solution of the clear, reasonable expectations as key driving forces of the academic success. On the other hand, in China which is place where collectiveness, honor, authority and superiority in studies are highly esteemed, mostly mothers follow more authoritative but deeply involved in children upbringing. These measures highlight the importance of discipline, respect for elders and exemplary academic courses (Xu & Yao, 2015). Though this style is believed to apply pressure on children, it is sometimes linked to the high academic performance and thus shows how the culture, parenting practices and education are interconnected.

2.4. Self-efficacy and academic self-efficacy

Recently research to provide a comprehensive understanding of self-efficacy and academic self-efficacy, their definitions, implications, and influencing factors, offering valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and researchers. Extensive studies across various educational settings and skill levels have shown the significant impact of self-efficacy on learning behavior, motivation, and academic achievement. Students with low self-efficacy tend to experience more academic anxiety, while those with high self-efficacy show better academic performance and reduce vulnerability to fatigue and depression (Bandura, 1986; Fariborz et al., 2019).

Additionally, academic self-efficacy is crucial for students within similar age groups, as it positively correlates with self-regulated learning skills and academic success, as demonstrated by Lee et al. (2014) in a study with 336 high school students.

Self-efficacy, and its crucial role in education, should serve as the basis for further investigations concerning the dynamics through which self-efficacy, mainly, academic self-efficacy, is developed and is influenced in the context of family and culture. In that case, Wang et al. (2020) studied how parental involvement and parenting styles are closely related to the development of children's self-efficacy beliefs. Particularly, authoritative parenting style, which includes high responsiveness and high demand, has been attributed to higher academic self-efficacy in students. The above parenting approach, which finds the ground for self-motivation and self-regulation, supports independence of students as they develop feeling of competence and self-confidence. Also, Zhang et al. (2023) indicated that investigation of academic self-efficacy in the context of cultural differences is essential. Cultural values and standards very often direct the formation of self-efficacy beliefs. For example, in cultures which highly value educational achievement and provide organized learning environments like in the case of most East Asian countries, children tend to have higher academic self-efficacy. However, this is partly caused by the community promotion of outstanding achievements, discipline, and the society appreciating the academic gap as a route to individual and family improvement (Zhang et al., 2017).

On one side, cultures such as those in the West that highlight individualism and self-interest, might be the route to academic self-efficacy when it fosters experiential learning and personal achievements. The numerous approach to defining academic success and the diverse cultural preferences of students further highlight the fact that academic self-efficacy cannot only be attributed to personal capability but it is rather deeply rooted in social and cultural settings (Fong & Yuen, 2016).

Moreover, this influence is not limited to academic performance only. The student bearing high academic self-efficacy is more likely to be able to set up achievable objectives, use effective strategies to overcome difficulties and avoid to give up when facing the challenges. The activities have the intentions to practice having a growth mindset and a learning style that is active, and that is fundamental for success in complicated and ever-changing educational settings (DiBenedetto & Schunk, 2018). Self-efficacy, parenting styles, and cultural backgrounds reveal the complexity of educational psychology underscoring the need for an individualized approach in order to attain academic success. Educators and policymakers need to recognize the multifaceted nature of factors that impact academic self-efficacy and then come up with interventions that can help the development of such beliefs (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016, 2021). Education programs culturally designed and parent's options in consideration improves the effectiveness of these programs and is one of the main keys to the success of the students both academically and personally.

2.5. Academic self-efficacy, parenting style and performance

Academic self-efficacy is influenced by various factors, including a positive and caring home environment provided by parents, which fosters adaptive internal motivation and enhances academic performance (Fan & Williams, 2010). A study with 500 Spanish adolescents revealed a link between parenting style and academic self-efficacy, with the maternal permissive style predicting aggressive behavior (Llorca et al., 2017). However, the impact of parenting style on academic self-efficacy may diminish as students age, with authoritative parenting continuing to influence college students' academic performance (Turner et al., 2022).

Cultural background also plays a role, as demonstrated by Aldhafri et al. (2020), who found that parenting style's influence on self-efficacy decreases with age, based on a study with Omani school and university students. This indicates developmental changes in students' perceptions of their academic effectiveness. Academic performance, often measured through exam results, is closely linked to academic self-efficacy.

Students with high academic self-efficacy tend to perform better academically (Bandura, 1986; Huang & Gove, 2009; Schunk, 1983). Furthermore, a case study by Lian on students with academic disabilities found that improving academic self-efficacy significantly enhanced academic performance.

According to Masud et al. (2016), the interaction between academic self-efficacy, parenting style and academic results, signifies the complicatedness of educational outcomes. A more thorough look into these interdependencies exposes the complicated way in which the factors combine to create a student's overall academic experience. It surely is evident that parental support is a crucial factor that a student needs to develop academic self-efficacy. This setting is achieved through various parenting styles that don't only provide for emotional warmth and support but as well as make students active players in their studies. Moreover, in contrast to Llorca et al. (2017), parenting styles influence academic self-efficacy as they vary from cultural context. To illustrate, in cultures where education is viewed very highly and parents' involvement is stressed, as in most Asian societies, the expectations placed on children could result in increased academic self-efficacy. Such children are often subject to the same consistent messages about the significance of academic excellence, along with the assistance and resources necessary for achieving it.

On the other side, in cultures where the balance between personal development and individual interests is as important as the academic achievement parents’ style of parenting might be associated with academic self-efficacy in a different way. It may be the case in such environments that pediatric academic self-efficacy can be developed by autonomy-supportive parenting where the child can explore and learn on its own (Yuan et al., 2016).

This empowerment when combined with proper guidance prepares students in a way that they can overcome even the toughest of challenges with the ability to learn from their mistakes, obstacles in their way can be seen as opportunities to become better instead of insurmountable obstacles. Moreover, the process of academic self-efficacy changes over a lifetime reveals a complex relationship between a person's development and external factors (Theresya et al., 2018). Students have often felt their self-confidence shift from parents and teachers to a broader range of their life experiences when they become young adults. They could involve experiences such as professional successes, peer interactions or other social issues. (Gebauer et al., 2021). This developmental perspective, therefore, brings up the need for interventions aimed at strengthening academic self-efficacy since it has to be matched with the specific requirements of students at different stages of education.

3. Methods

3.1. Introduction

A quantitative analysis, the quickest and most efficient survey method, was used for data collection through an online survey sent to university students from different countries, including a review of both traditional and electronic literature. Such an approach involved automated processes and digital tools that made global participation possible. The research looked into professional works about parenting styles and academic self-efficacy in both Spanish and Chinese environments, folding out a completely comprehensive collection of references which spanned not only journal articles but also masters and PhD theses from a massive range of data sources, including CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) and English academic paper sites. In addition to this, the research was based on the relevant laws, regulations and news highlights which the state issued to make the research ground richer.

3.2. Survey

This research used a sample survey emphasizing the effect of mothers' parenting styles and self-efficacy on academic achievement referring to Chinese and Spanish university students. Students' cultural backgrounds and their own families were examined with the use of sample methods. The questionnaires provided data concerning students` performance and their experiences of their mothers parenting and self-efficacy, while quantitative methods analyzed their current and past environments.

3.3. Participants

This study involved participants from Sha’anxi University of Technology (X University) in China and the University of Lleida (L University) in Spain, with 100 students from each university, covering both genders. The two institutions provide courses for preschool and primary education at the undergraduate level, with only variations in the settings curriculum as, for eg, Spain's double degree system which last for 5 years. The academic calendars are also different; China runs from September to the mid-January and from the middle of February to June, while Spain goes from September to December and from January to June. Online surveys used in the research were distributed to students from both faculties after obtaining special course teachers' permission.

Along with the balanced gender distribution of our participants, social-demographic breakdowns have been researched as well to produce a more comprehensive picture of the study sample. This additional information includes age, field of study, year of study and socioeconomic background. The ages of the participants are spread from 18 to 25, which demonstrates the usual undergraduate population. The focus of study is pre-school and primary education although most participants are specializing in their respective programs due to the cross-cutting nature of the field of study. The period of year changes from first-year undergraduates through to students approaching completion of studies, reflecting the academic progression and university life at various stages of the education process.

The socioeconomic background data was collected through a set of questions with the purpose to uncover the extent to which familial socio-economic status can affect students' academic self-efficacy and performance.

3.4. Measures

The study utilized the condensed S-EMBU version of the "Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran" (EMBU) questionnaire, developed by Perris et al. (1980) in Sweden, to assess mothers' parenting styles across three dimensions: the warmth of love, humiliation, and spoiling. Through the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale that has 26 items, it is possible to determine how these experiences may affect an adult's psychological wellbeing and personality development, and it has been translated in many languages since it spread to all over the world. In order to establish the relationship between mothers' parenting styles and students' academic self-efficacy, and provide data on academic performance, such a well-known means was used. Academic performance was measured with mid-term and final exam scores of 2021-2022 academic year, and the mid-term and final professional courses' results. The processed and analyzed data were conducted using SPSS 26.0 with difference tests, correlation analyses, and regression analysis as statistical methods. In adapting the S-EMBU questionnaire for this study, certain modifications were made to better align with our research objectives and the context of the participants. Specifically, question 15 from the original questionnaire, which pertains to family size and dynamics, was omitted to control for variables and exclude families with numerous children, considering the potential impact of these factors on the parenting styles assessed. This adjustment was made to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the data collected in relation to the study's focus on parenting styles and their correlation with academic self-efficacy and performance.

3.5. Parenting Style Questionnaire: Mothers' Parenting Style

In this study, the S-EMBU scale was used to ensure credibility, focusing solely on mothers' parenting styles by removing items related to fathers. The questionnaires were translated into Spanish and Chinese, and thoroughly proofread before being distributed. To control for variables and exclude families with numerous children, question 15 from the original test was omitted. Additionally, to address the complexity of guilt as a human experience and differentiate between healthy and unhealthy guilt, question 10 was also removed. Table 1 outlines the distribution of topics in the scale, categorizing them into rejection (1,4,5,7,12,14,19), emotional warmth (2,6,11,13,17,21), and protection (3,5,8,10,15,16,18,20).

| Questions | No of items | |

| Rejection | 1,4,5,7,12,14,19 | 7 |

| Emotional Warmth | 2,6,11,13,17,21 | 6 |

| Protection | 3,5,8,10,15*,16,18,20 | 8 |

3.6. Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

The Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire used in this study, developed by Zhou and Liang, employed the adapted version due to its demonstrated reliability in previous studies. The data were analyzed by SPSS 26.0 software. The questionnaire contains 24 items, which are divided into two categories: learning behavior and learning ability, with 11 items. A 5-point scoring method was applied, ranging from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 5 (completely consistent). The total score was calculated by summing the scores of each question, representing the student's self-efficacy score. Academic performance was assessed by mid-term and final exams in the 2021-2022 academic year, with the abbreviation "S" representing scores in mid-term and final professional courses.

3.7. Composite Reliability of Mothers' Parenting Styles and Academic Self-Efficacy Scales

Cronbach's coefficient, ranging from 0 to 1, assesses scale reliability, with values above 0.7 indicating good internal consistency and values below 0.6 suggesting the need for revision. In this study, the mothers' parenting styles and Academic Self-Efficacy scales both showed good internal consistency, with coefficients of 0.77 and 0.76 respectively, as displayed in Table 2.The study delves into the overarching constructs of Mother's Parenting Style and Self-Efficacy, further dissecting the parenting construct into three sub-dimensions: Rejection, Emotional Warmth, and Protection, to offer a thorough understanding.

| Cronbach's | |

| Parenting | 0.77 |

| Rejection | 0.80 |

| Emotional Warmth | 0.80 |

| Protection | 0.71 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.76 |

4. Results

4.1. Situation of Mothers' parenting style

The study analyzes differences in mothers' parenting styles across countries, focusing on three dimensions: emotional warmth (positive), rejection, and overprotection (negative). Higher scores indicate a greater likelihood of a mother adopting a specific parenting style. In Spain, the mean scores for rejection and protection are 1.46 and 1.94, both below the median of 2.50, while emotional warmth scores higher at 3.24. This indicates a prevalent use of the emotional warmth parenting style among college mothers in Spain.

Table 3 shows that Spanish mothers predominantly express their maternal warmth through emotional warmth, with an average score of 3.24 ('M' represents the average score per question).

| Parenting Style | Metric | Spain | China |

| Rejection | Min | 7.00 | 6.00 |

| Max | 21.00 | 22.00 | |

| Mean | 10.23 | 16.86 | |

| SD | 3.52 | 2.82 | |

| Median (M) | 1.46 | 2.41 | |

| t-value | -14.70 | ||

| Emotional Warmth | Min | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| Max | 24.00 | 21.00 | |

| Mean | 19.44 | 16.50 | |

| SD | 3.59 | 3.27 | |

| Median (M) | 3.24 | 2.75 | |

| t-value | 8.21 | ||

| Protection | Min | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Max | 25.00 | 24.00 | |

| Mean | 15.52 | 13.84 | |

| SD | 3.99 | 2.96 | |

| Median (M) | 1.94 | 1.73 | |

| t-value | 4.51 |

Moreover, the table reveals that Chinese mothers select both rejection and emotional warmth as their parenting styles. The mean scores for rejection and overprotection dimensions are 2.41 and 1.73, respectively, both below the median level of 2.50. However, the emotional warmth dimension has a mean score of 2.75, which is above the median level of 2.50. This indicates that a substantial number of Chinese college mothers currently adopt the emotional warmth parenting style, along with some elements of rejection.

4.2. Cross-Country Differences in Mothers' Parenting Styles

| Parenting Style | Difference Significance | Remarks | t-value |

| Emotional Warmth | Insignificant | Minor differences observed | 8.21 |

| Over-Protection | Insignificant | Minor differences observed | 4.51 |

| Rejection | Highly Significant | Major differences observed; substantial disparity | -14.70 |

Table 4 demonstrates the varying degrees of difference in the parenting styles of university student mothers between China and Spain. The distinctions in the dimensions of emotional warmth and over-protection are relatively insignificant compared to the other dimensions. Consequently, there is a significant difference in the rejection parenting style of mothers. A t-value of -14.70 signifies a highly significant disparity between the two data sets. Generally, the larger the t-value (positive or negative), the more substantial the difference between the two sets of data.

4.3. Current State of Academic Self-efficacy

As shown in Table 5, the academic self-efficacy score of Spanish university students is 2.64, slightly above the average of 2.50, indicating that it hovers around the average. Moreover, the table reveals that the academic self-efficacy score of Chinese university students is 2.42, which is below the 2.50 average, suggesting a lack of motivation for self-efficacy among Chinese university students. However, the data indicates that it is only marginally lower and still around the average.

| Metric | Spain | China |

| Min | 34 | 22 |

| Max | 76 | 74 |

| Mean | 57.98 | 53.25 |

| SD | 8.39 | 11.92 |

| Median (M) | 2.64 | 2.42 |

| Spain | China | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Academic | 57.98 | 8.39 | 53.25 | 11.92 | 7.421 |

Table 6 compares the results from the two different cultural backgrounds. The study analyzed the current development of academic self-efficacy among university students in both countries by making descriptive statistics of the total and dimensional scores of the academic self-efficacy measure. According to Table 6, the differences in academic self-efficacy among university students are generally significant. A t-value of 7.421 indicates that the difference between the two sets of data is significant. Generally, the larger the t-value (positive or negative), the more substantial the difference between the two data sets.

In summary, these findings reveal a marked contrast in mothers’ parenting styles and academic self-efficacy levels between Chinese and Spanish university students.

4.4. Research on the Relationship Among Mothers’ Parenting Style, Academic Self-efficacy and Academic Achievement

Tables 7 and 8 reveal the relationships between mothers' parenting styles, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement in Spain and China. Warm parenting correlates with higher academic achievement, while rejection correlates with lower achievement. There is a positive and significant correlation between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement in both countries, showing consistency in the relationship between academic self-efficacy and mothers' parenting styles across different cultural contexts.

| Rejection | Emotional Warmth | Protection | Academic | Score | |

| Rejection | 1.00 | -0.24 | 0.65* | -0.35* | -0.27* |

| Emotional Warmth | -0.24 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.67* | 0.57* |

| Protection | 0.65* | 0.13 | 1.00 | -0.22 | -0.11 |

| Academic | -0.35* | 0.67* | -0.22 | 1.00 | 0.72** |

| Score | -0.27* | 0.57* | -0.11 | 0.72** | 1.00 |

| Rejection | Emotional Warmth | Protection | Academic | Score | |

| Rejection | 1.00 | -0.14 | 0.72* | -0.31* | -0.35* |

| Emotional Warmth | -0.14 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.53* | 0.51* |

| Protection | 0.72* | 0.21 | 1.00 | -0.12 | -0.15 |

| Academic | -0.31* | 0.53* | -0.12 | 1.00 | 0.77** |

| Score | -0.35* | 0.51* | -0.15 | 0.77** | 1.00 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Different Country in Parenting Styles of Mothers

The previous evaluation reveals that there is a disparity between countries in terms their parenting styles where Spanish mothers usually show more emotional warmth than Chinese mothers. In addition, the analysis illustrates Chinese parents use more stringent and punitive parenting methods possibly because of the competitive nature of their education system and the high rating of academic achievement. This shows the extent to which exam-oriented approach is popular in China, which in turn causes intensive pressure and strict expectations on children. The root of the discrepancy in the parenting styles of Spain and China is somewhere in the culture, society and history. Mesurado et al. (2014) report that the Spanish parenting style is based on emotional warmth that is rooted in the cultural value of close family ties, emotional expression, and nurturance. The Spanish society usually encourages a holistic approach to education that focuses not only on academic success but also on emotional wellbeing and social development. On the other hand, Huang and Gove (2015) argued that the Chinese parenting style is rooted in the country’s Confucian tradition, which emphasizes obedience, respect for authority, and education. The ultra-competitive structure of the Chinese education system that puts a lot of emphasis on exams and academic performance, is the source of the rigidity and emphasis on education outcomes of Chinese parents. Many Chinese parents believe that the key to school success for their kids includes rigorous discipline and high-demanding expectations.

5.2. Different country in academic self-efficacy

The analysis shows that there aren't significant differences in academic self-efficacy among students from the two countries, which means that the data does not offer an irrefutable analysis as well. This should therefore be due to the similarities between the Spanish and the Chinese students who study in comprehensive universities of the same types and are situated in provinces with the same economic strength. Course content and difficulty level do not differ there, and they are of similar age. The student's mastery of education is generally similar, and their academic self-concept is the same across the countries. However, Schwarzer et al. (1997) point out that behind academic self-efficacy among Spanish and Chinese students there may be diverse cultural and educational issues which might affect their perception. Despite the results of the research revealing no substantial disparities in academic self-efficacy between these two groups, several causes can be considered for the possible outcome.

Cultural views on self-efficacy might be different but might be not gauged by the data. Besides, Rosenthal and Feldman (1991, 2016) mentioned that the cultural beliefs and values of education, achievement, and personal competence can have the largest effect on students' self-concept. For instance, in the case of collectivist cultures such as China, students are always more likely to attribute their academic success to external factors like effort and perseverance rather than natural intelligence. On one side, the research addressed to the university students may omitted differences in academic self-efficacy which could appear earlier in the educational journey. Culturally different parenting styles, educational modes, and societal expectation could make students believe in their academic abilities right from the childhood and this belief could turn into their self-efficacy as they move through the education system.

5.3. The Relationship Between Mothers' Parenting Style, Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Achievement

The analysis shows a significant relationship between emotional warmth, rejection, and academic achievement, aligning with Kim et al. (2013) findings that supportive parenting enhances academic performance. Students nurtured with care tend to excel academically, as a positive environment is crucial for development. In contrast to positive parenting, overly negative parenting hinders academic success, resulting in stress and a poor learning environment. In addition, the analysis shows a strong positive relationship between the academic self-efficacy and the achievement, therefore, students who are confident of their abilities tend to perform better in academics. It is because the students are always confident in handling the challenges of learning, keeping perseverance even during the face of failure, and attributing failure to external factors rather than their own abilities. It is this resilience that then translates to higher academic performance.

It additionally shows an intriguing connection between parenting style and the students' confidence in learning. It implies their parenting behaviors, like warmth or rejection could correlate with students' thoughts on their academic potential. Here the children who have high amounts of emotional closeness with their mum may develop really strong self-beliefs in their capacity to excel in academics and this actually leads to their academic self-efficacy being high. However, the kids who face rejection or lack support from their moms perform poorly on the issue of the academic self-efficacy that, later on, affects their academic performance. This illustration emphasizes the significance of parent’s participation and assistance in forming the beliefs of students regarding their academic competencies. In summary, the study highlights the complex interaction involved in parenting style, academic self-efficacy, and academic performance. It implies that if parents give the correct amount of love and support to their children this can affect academic self-efficacy and achievement very positively, reflecting the prominent role of parents in their children’s success in school.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Encouraging Positive Parenting Styles Among Mothers

While academic self-efficacy is not related to culture, Spanish mothers appear to be more warm, while Chinese are more likely to use negative styles of parenting. It is important to bear in mind that different approaches of parenting exist and what works Best for one family might not work for another. What is important is to create a secure, supportive setting and, at the same time, to adjust the style of your communication to the needs of your child. Stress that grades are not everything and think about their individual needs and temperament before you choose a parenting style. Some pupils respond to authoritarian style of teaching very well, while others need a permissive style of teaching. Make sure that you communicate clearly with your child, set reasonable limits, and keep flexibility to manage the needs of your child.

6.2. Enhancing School-family Collaboration

Communication between universities and families is essential to gain a comprehensive understanding of the child's life and psychological situation at school and home. Parents and teachers can collaborate to address the root causes of low academic achievement, guiding students towards effective learning strategies and building their confidence and academic self-efficacy. University students often experience isolation and withdrawal due to lack of attention, leading to lost confidence in their academic abilities, fear of studying, struggle with interpersonal communication, and difficulty interacting appropriately with peers. Both families and schools should closely monitor students' mental health to prevent them from developing psychological problems.

6.3. Providing Regular Guidance for Parents

The data indicates that a mix of parenting style and academic self-efficacy predicts academic success, emphasizing the importance of enhancing students' academic self-efficacy. Despite most college students living away from home, mothers' parenting style remains crucial for developing academic self-efficacy in both China and Spain, also contributing to academic success. In China, universities could hold parent meetings and guide parents through online or offline channels to foster positive parenting styles. Similarly, Spanish schools could engage parents in various activities, strengthening parent-child relationships and enhancing student management and education.

7. Limitations

This study employs empirical methods to explore the relationship among mothers' parenting styles, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement, providing theoretical guidance despite some limitations. Small Sample Size. However, the limited sample size may not provide comprehensive data, and the subjects may not fully represent the national situation in either country. Focus on Specific Student Group. The study mainly targets university students in two countries, excluding students from other educational stages and majors. Additionally, the examination of large regional differences may somewhat affect the results. Future research could address these limitations by expanding the sample size, including diverse educational stages and majors, and considering additional regional factors for a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between parenting styles, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement.

8. Bibliography

Aldhafri, S.S., Alrajhi, M.N., Alkharusi, H.A., Al-Harthy, I.S., Al-Barashdi, H.S. & Alhadabi, A.S. (2020). Parenting Styles and Academic Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Omani School and University Students. Education Sciences, 10(9), 229. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090229

Aluja, A., del Barrio, V. & Garcia, L.F. (2006). Comparison of several shortened versions of the EMBU: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(1), 23-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00489.x

Andrés-Cabello, S. (2023). Atención y trabajo de la diversidad cultural: familias de origen extranjero y gitano en un centro de especial dificultad. EHQUIDAD. Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, 20, 247-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.15257/EHQUIDAD.2023.0020

Arrindell, W. A., Sanavio, E., Aguilar, G., Sica, C., Hatzichristou, C., Eisemann, M., Recinos, L. A., Gaszner, P., Peter, M., Battagliese, G., Kállai, J. & Van der Ende, J. (1999). The development of a short form of the EMBU: Its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and Italy. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(4), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00192-5

Arrindell, W.A., Akkerman, A., Bagés, N., Feldman, L., Caballo, V.L., Tian, P.S., Oei, B.T., Canalda, G., Castro, J., Montgomery, I., Davis, M., Calvo, M.G., Kenardy, J.A., Palenzuela, D.L., Richards, J.C., Leong, C.C, Simón, M.A. & Zaldívar, F. (2005). The Short-EMBU in Australia, Spain, and Venezuela. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(1), 56-66. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.21.1.56

Baidi, B. (2019). The Role of Parents’ Interests and Attitudes in Motivating Them to Homeschool Their Children. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 10, 156-177.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Baumrind D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 1–103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0030372

Baumrind, D. (1991). The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Competence and Substance Use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431691111004

Benish-Weisman, M., Oreg S. & Berson, Y. (2022). The Contribution of Peer Values to Children’s Values and Behavior. Personality & social psychology bulletin, 48(6), 844–864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01461672211020193

Cheah, C.S.L., Leung, C.Y., Tahseen, M. & Schultz, D. (2009). Authoritative parenting among immigrant Chinese mothers of preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(3), 311-320. http://dx.doi.org/:10.1037/a0015076

Chen, Y. (2016). Chinese parents' perspectives on parenting: children's education and future prospects (Master's thesis, Itä-Suomen yliopisto).

Chen, S.H., Zhou, Q., Main, A. & Lee, E.H. (2015). Chinese American immigrant parents’ emotional expression in the family: Relations with parents’ cultural orientations and children’s emotion-related regulation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 619-629. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000013

Chen, X., Liu, M., Li, B., Cen, G., Chen, H. & Wang, L. (2000). Maternal authoritative and authoritarian attitudes and mother-child interactions and relationships in urban China. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24(1), 119-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502500383557

Cline, F. & Fay, J. (2020). Parenting with Love and Logic. NavPress.

DiBenedetto, M. K., & Schunk, D. H. (2018). Self-efficacy in education revisited through a sociocultural lens. Big theories revisited, 2(5), 117-131.

Doepke, M. & Zilibotti, F. (2017). Parenting with style: altruism and paternalism in intergenerational preference transmission. Econometrica. Journal of Econometric Society, 85(5), 1331–1371. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14634

Emerson, R.W. (2019). Cronbach's Alpha Explained. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 113(3), 327-328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X19858866

Errasti Pérez, J.M., Amigo Vázquez, I., Villadangos Fernández, J. M. & Morís Fernández, J. (2018). Differences between individualist and collectivist cultures in emotional Facebook usage: Relationship with empathy, self-esteem, and narcissism. Psicothema, 30(4), 376-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.101

Fan, W. & Williams, C.M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self‐efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903353302

Fariborz, N., Hadi, J. & Ali, T. N. (2019). Students’ academic stress, stress response and academic burnout: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 27(4), 2441-2454.

Fong, R.W. & Yuen, M.T. (2016). The role of self-efficacy and connectedness in the academic success of Chinese learners. In The psychology of Asian learners: A festschrift in honor of David Watkins (pp. 157-169). Springer Singapore.

García F. & Gracia E. (2009). Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence Roslyn Heights, 173(44), 101-131.

García, O.F., Serra, E., Zacarés, J.J. & García, F. (2018). Parenting styles and short-and long-term socialization outcomes: A study among Spanish adolescents and older adults. Psychosocial Intervention, 27(3), 153-161. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2018a21

Gebauer, M.M., McElvany, N., Köller, O. & Schöber, C. (2021). Cross-cultural differences in academic self-efficacy and its sources across socialization contexts. Social Psychology of Education, 24(6), 1407-1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09658-3

Gestwicki, C. (2016). Home, school & community relations. Ma: Cengage Learning.

Greco, A., Annovazzi, C., Palena, N., Camussi, E., Rossi, G. & Steca, P. (2022). Self-Efficacy Beliefs of University Students: Examining Factor Validity and Measurement Invariance of the New Academic Self-Efficacy Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.498824

Harris, J. (2010). Why Parents do not matter. In F.T. Cullen & P. Wilcox. Encyclopedia of Criminological Theory (pp. 432-435). SAGE Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412959193.n118

Herrmann-Pillath, C. (2016). Fei Xiaotong's comparative theory of Chinese culture: Its relevance for contemporary cross-disciplinary research on Chinese'collectivism'. The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, 34(1), 25-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.22439/cjas.v34i1.5187

Honicke, T. & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002

Huang, G.H.C. & Gove, M. (2015). Confucianism, Chinese families, and academic achievement: Exploring how Confucianism and Asian descendant parenting practices influence children’s academic achievement. In Khine, M. (ed.), Science education in East Asia: Pedagogical innovations and research-informed practices (pp. 41-66). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16390-1_3

Jinping, X. (2017, October). Secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and strive for the great success of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era. In delivered at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China October (Vol. 18, 7-11).

Julian, M.M. (2013). Age at adoption from institutional care as a window into the lasting effects of early experiences. Clinical child and family psychology review, 16, 101-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0130-6

Keller, H., Borke, J., Chaudhary, N., Lamm, B. & Kleis, A. (2010). Continuity in Parenting Strategies: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109359690

Kim, S.Y., Wang, Y., Orozco-Lapray, D., Shen, Y. & Murtuza, M. (2013). Does “tiger parenting” exist? Parenting profiles of Chinese Americans and adolescent developmental outcomes. Asian American journal of psychology, 4(1), 7-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030612

Lee, W., Lee, M.J. & Bong, M. (2014). Testing interest and self-efficacy as predictors of academic self-regulation and achievement. Contemporary educational psychology, 39(2), 86-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.02.002

Li, M.G. (2020). A case work to solve the problem of college students' academic achievements to try (Unpublished Master's degree thesis). Soochow University (Suzhou, Jiangsu, China).

Li, M.R (2019). The college students' psychological adaptation of the native family impact study (Unpublished Master's degree thesis). Central China Normal University.

Liu, S.L. & Chen, K.W. (2020). The Relationship between Interpersonal Skills and Family Upbringing of College Students: A Case study of zk College. Youth and Society, 28, 173-174.

Llevot, N. & Garreta, J. (2024). Intercultural mediation in school. The Spanish education system and growing cultural diversity. Educational Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2024.2329894

Llevot, N. & Bernad, O. (2019). Diversidad cultural e igualdad de oportunidades en la escuela de Cataluña (España): retos y desafios. Revista Educazione Interculturale, Teorie, Ricerche, Pratiche, 17(2), 76-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.14605/EI1721906

Llevot, N. & Bernad, O. (2021). La mediación cultural y prácticas educativas en Italia. Ehquidad. Revista Internacional de Políticas del Bienestar, 16, 209-246. https://doi.org/10.15257/ehquidad.2021.0020

Llorca, A., Cristina Richaud, M. & Malonda, E. (2017). Parenting, Peer Relationships, Academic Self-efficacy, and Academic Achievement: Direct and Mediating Effects. Frontiers in psychology, 15(8), 2120. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02120

Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2020). Participants: Children, Their Families and Socialization Contexts. In The Multilingual Adolescent Experience: Small Stories of Integration and Socialization by Polish Families in Ireland. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

Masud, H., Ahmad, M.S., Jan, F.A. & Jamil, A. (2016). Relationship between parenting styles and academic performance of adolescents: mediating role of self-efficacy. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17, 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9413-6

Mesurado, B., Richaud, M.C., Mestre, M.V., Samper-García, P., Tur-Porcar, A., Morales Mesa, S.A. & Viveros, E.F. (2014). Parental expectations and prosocial behavior of adolescents from low-income backgrounds: A cross-cultural comparison between three countries—Argentina, Colombia, and Spain. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(9), 1471-1488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114542284

Nguyen, A.M.D., Jefferies, J. & Rojas, B. (2018). Short term, big impact? Changes in self-efficacy and cultural intelligence, and the adjustment of multicultural and monocultural students abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 66, 119-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.08.001

Ortiz, F. A. (2020). Self-actualization in the Latino/Hispanic culture. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(3), 418-435. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678177417

Pasquarella, A., Chen, X., Gottardo, A. & Geva, E. (2015). Cross-language transfer of word reading accuracy and word reading fluency in Spanish-English and Chinese-English bilinguals: Script-universal and script-specific processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 96-110. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036966

Perris, C., Jacobsson, L., Linndström, H., Von Knorring, L. & Perris, H. (1980). Development of a new inventory for assessing memories of parental rearing behaviour. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 61(4), 265-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00581.x

Rosenthal, D.A. & Feldman, S.S. (2016). The Influence of Perceived Family and Personal Factors on Self-Reported: School Performance of Chinese and Western High School Students. In Cognitive and Moral Development, Academic Achievement in Adolescence (pp. 197-216). Routledge.

Rosenthal, D. A. & Feldman, S. S. (1991). The Influence of Perceived Family and Personal Factors on Self-Reported School Performance of Chinese and Western High School Students. Journal of Research on Adolescence, .(2), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0102_2

Sandoval-Palis, I., Naranjo, D., Vidal, J. & Gilar-Corbi, R. (2020). Early Dropout Prediction Model: A Case Study of University Leveling Course Students. Sustainability, 12(22), 9314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229314

Sahithya B.R. & Vijaya Raman (2021). Influence of parental personality on parenting styles: A scoping review of literature. International Journal of Psychology Sciences, 3(1), 4-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.33545/266 48377.2021.v3.i1a.22

Sijia, D. & Yaoujun, L. (2023). Unequal parenting in China: A study of socio-cultural and political effect. Sociological Review. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261231198329

Schunk, D. H, & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2021). Self-efficacy and human motivation. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (pp. 153–179). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2020.10.001

Schunk, D.H. & DiBenedetto, M.K. (2016). Self-efficacy theory in education. In Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 34-54). Routledge.

Schwarzer, R., Bäßler, J., Kwiatek, P., Schröder, K. & Zhang, J.X. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self‐beliefs: comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self‐efficacy scale. Applied psychology, 46(1), 69-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14640597.1997.tb01096.x

Shengyao, Y., Salarzadeh Jenatabadi, H., Mengshi, Y., Minqin, C., Xuefen, L. & Mustafa, Z. (2024). Academic resilience, self-efficacy, and motivation: the role of parenting style. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 5571. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55530-7

Theresya, J., Latifah, M. & Hernawati, N. (2018). The effect of parenting style, self-efficacy, and self regulated learning on adolescents’ academic achievement. Journal of Child Development Studies, 3(1), 28-43.

Tremblay, K., Lalancette, D., & Roseveare, D. (2012). Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes: Feasibility Study Report. In Volume 1–Design and Implementation (pp.190-193). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). http://www.oecd.org/edu/highereducationandadultlearning/AHELOFSReportVolume1.pdf

Turner, M. J., Miller, A., Youngs, H., Barber, N., Brick, N. E., Chadha, N. J., … Rossato, C. J. L. (2022). “I must do this!”: A latent profile analysis approach to understanding the role of irrational beliefs and motivation regulation in mental and physical health. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(8), 934–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2022.2042124

Van Voorhis, F.L., Maier, M.F., Epstein, J.L. & Lloyd, C.M. (2013). The impact of family involvement on the education of children ages 3 to 8: A focus on literacy and math achievement outcomes and social-emotional skills. MDRC, Building knowledge to improve social policy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED545474.pdf

Wang, G. (2022). Analysis on the relationship between psychological adaptability of post-00s college students and their family of origin. Journal of fujian teachers university of technology, 02, 198-206, 225. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.884016

Wang, M.T., Guo, J. & Degol, J.L. (2020). The role of sociocultural factors in student achievement motivation: A cross-cultural review. Adolescent Research Review, 5(4), 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00124-y

Xiao, B., Bullock, A., Coplan, R.J., Liu, J. & Cheah, C.S. (2021). Exploring the relations between parenting practices, child shyness, and internalizing problems in Chinese culture. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(6), 833. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000904

Xu, Y. & Yao, Y. (2015). Informal institutions, collective action, and public investment in rural China. American Political Science Review, 109(2), 371-391. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000155

Yao, J.J. (2017). The causes and educational strategies of college students' poor academic performance -- based on the analysis of an engineering school in Fujian Province. Journal of Kaifeng Institute of Education, (03), 149-150.

Young, I.F., Razavi, P., Cohen, T.R., Yang, Q., Alabèrnia-Segura, M. & Sullivan, D. (2021). A multidimensional approach to the relationship between individualism-collectivism and guilt and shame. Emotion, 21(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000689

Yuan, S. (2022). Students school failure of early warning and response (Ph.D. Thesis, Ttianjin Normal University). 554469.nh

Yuan, S., Weiser, D.A. & Fischer, J.L. (2016). Self-efficacy, parent–child relationships, and academic performance: A comparison of European American and Asian American college students. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 261-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9330-x

Yuan Li, Dan Feng, Yu Zhang, Mei Zhang, Qingqing Zheng, Xiao Wei (2022). A Study on the Relationship between Family Rearing Styles and Preschool Children's Prosocial Behavior. International Journal of New Developments in Education, 4(11), 54-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.25236/IJNDE.2022.041111

Yue, D.M., Li, M.G., Jin, K.H., et al. (1993). Parental rearing style:a preliminary revision of EMBU and its application in neurosis patients[J]. Chin Mental Health Journal, 7(3), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2019.2

Zhang, Y. & Kong, L. (2019). A study on the relationship between college students' interpersonal skills and family rearing styles. Journal of Mudanjiang Normal University (Social Sciences Edition), 03,102-106.

Zhang, L. Jiang, Y., & Chen, S. (2023). Longitudinal interrelations among self-efficacy, interest value, and effort cost in adolescent students’ English achievement and future choice intentions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102176

Zhang, W., Wei, X., Ji, L., Chen, L. & Deater-Deckard, K. (2017). Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 1117-1136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0664-x

Zhao, H.R. (2017). Psychological adjustment of college students: The influence of the family of Origin (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Soochow University (Suzhou, China).

Zhao, S., & Cao, C. (2023). Exploring Relationship Among Self-Regulated Learning, Self-Efficacy and Engagement in Blended Collaborative Context. Sage Open, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231157240

Zhou N, Cheah C.S., Van Hook J., Thompson D.A. & Jones S.S. (2015). A cultural understanding of Chinese immigrant mothers' feeding practices. A qualitative study. Appetite, 87, 160-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.12.215

Zimmerman, B. J. & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of Self-Regulatory Influences on Writing Course Attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163397

Información adicional

Referencia normalizada:: Xin, X. (2024). Mothers’s Parenting Styles, Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance: Chinese-Spanish Cross Cultural Study. Ehquidad. International Welfare Policies and Social Work Journal, 22, 215-254. https://doi.org/ 10.15257/ehquidad.2024.0018