Artículos

Beyond Borders: A Qualitative Analysis of Migrant Health and Sociodemographics

Beyond Borders: A Qualitative Analysis of Migrant Health and Sociodemographics

Ehquidad: La Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, núm. 22, pp. 181-214, 2024

Asociación Internacional de Ciencias Sociales y Trabajo Social

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 21 Febrero 2024

Revisado: 27 Marzo 2024

Aprobación: 01 Abril 2024

Publicación: 22 Abril 2024

Abstract: Migration and health are integral aspects of human nature that are high on global policy agendas. In this context, it is crucial to delve deeper into the study of migration as it relates to physical health in order to explore some dimensions in greater depth. The objectives of this study are as follows 1) To explore the perceptions of migrants, participants in the study, about their health. Focusing on aspects related to physical health, disabilities and access to health care services; 2) To identify and describe the distinctive features that characterise the migrant population participating in the study. This analysis is carried out using a qualitative methodology based on the Grounded Theory approach. We employ tools such as individual records and group interviews to collect data. The primary findings of this study reveal the presence of pathologies and disabilities, alongside deficiencies in accessing healthcare services. Additionally, the key characteristics of migrants in Spain are highlighted. In conclusion, this study underlines the importance of maintaining the study of physical health in the context of migration from different disciplines as a way of underpinning social interventions aimed at improving the situation of migrants in the field of social and health welfare.

Keywords: Migration, Health, Sociodemographic Characteristics, Social Support, Qualitative.

Resumen: Migración y salud son aspectos integrales de la naturaleza humana que ocupan un lugar destacado en las agendas políticas globales. En este contexto, es crucial profundizar en el estudio de la migración en relación con la salud física para explorar algunas dimensiones con mayor detalle. Los objetivos de este estudio son los siguientes: 1) Explorar las percepciones de los migrantes, participantes en el estudio, acerca de su salud, centrándose en aspectos relacionados con la salud física, discapacidades y acceso a servicios de atención médica; 2) Identificar y describir las características distintivas que caracterizan a la población migrante participante en el estudio. Este análisis se realiza utilizando una metodología cualitativa basada en el enfoque de la Teoría Fundamentada. Empleamos herramientas como registros individuales y entrevistas grupales para recopilar datos. Los hallazgos principales de este estudio revelan la presencia de patologías y discapacidades, junto con deficiencias en el acceso a servicios de atención médica. Además, se destacan las características clave de los migrantes en España. En conclusión, este estudio subraya la importancia de mantener el estudio de la salud física en el contexto de la migración desde diferentes disciplinas como una forma de respaldar intervenciones sociales destinadas a mejorar la situación de los migrantes en el ámbito del bienestar social y de la salud.

Palabras clave: Migración, Salud, Características Sociodemográficas, Apoyo social, Cualitativo.

1. INTRODUCCTION

Throughout the history of humanity, migration has been a constant phenomenon that has played a fundamental role in the evolution of societies (United Nations, 2023). Its core meaning has remained largely unchanged as it represents a constantly moving process that drives the development of communities and arises in response to individual or family needs. Migration holds a transformative power that extends worldwide and often becomes a determining factor in the growth and development of countries (Lee, 1966, p. 47; Jiménez and Tprin, 2023, p. 13).

A clear example of this is the demand for labor, population growth, and talent diversification, challenges that are increasingly finding their solutions in migration. This makes migratory movements a recurring topic on international political and social agendas (Guerrero and Pérez, 2023, p.235).

Migration is defined as the displacement of people from their usual place of residence, whether within the borders of their home country or beyond, regardless of its scale, composition, or underlying reasons (International Organization for Migration, 2019). According to the United Nations (2022), these displacements or migrations can be driven by various reasons, including labor opportunities, family reunification, economic factors, pursuit of education, escape from conflicts, persecutions, terrorism, the impacts of climate change, and, ultimately, violations of human rights.

According to the "World Migration Report 2022" by the International Organization for Migration (2023), approximately 3.6% of the world's population currently resides in a place different from their birthplace, which equates to roughly 281 million international migrants. There has been a growing trend in the global number of migrants over the last five decades, with an increase of over 9 million international migrants between 2019 and 2020. However, it's important to note that this trend was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which reduced the population of international migrants by at least 2 million people (International Organization for Migration, 2023).

These data highlight the importance of recognizing that migration can result from a variety of push and pull factors, as commonly known, which explain that despite the benefits that migration can bring to both individuals and countries, it is not always a free choice. In many cases, migrations are driven by compelling needs, such as forced displacements, which currently affect over 79.5 million people worldwide (International Organization for Migration, 2023).

It's important to emphasize that Europe has become the primary destination for migrants, hosting 87 million migrants, which represents 30.9% of the global population of international migrants (IOM, 2023). Spain is one of the main migration destinations in Europe, having experienced significant growth since 2000, with an increase of 106 million cases compared to other European countries (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2023). Currently, Spain is home to 6.84 million migrants, equivalent to 14.6% of its total population. In 2022, a notable increase in the number of migrants was observed, with an additional 172,456 people. The main migrant groups originate primarily from Colombia (with an increase of 60,142 people), Ukraine (with an increase of 48,396 people), and Venezuela (with an increase of 31,703 people) (National Institute of Statistics, 2022). Additionally, it's important to mention figures related to applications for international protection in Spain, where only 10.5% of these applications are favorably resolved, falling well below the European average of 35% (Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid, 2023).

Health, as a fundamental element for life and human development, is defined by the World Health Organization (1946) as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being that goes beyond the absence of diseases. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) identifies health as a right that all individuals should have access to and that must be guaranteed, regardless of ethnicity, ideology, religion, etc. This right to health implies timely, acceptable, and affordable access to appropriate healthcare services.

Building upon these definitions and the state of the issue, it's evident that health, as a universal social right, also extends to migrant individuals. There is a clear connection between the migratory phenomenon and health, as demonstrated by previous research on the effects of migration on the health of migrants and refugees (Bozorgmehr et al., 2023, p.1). Additionally, the topic of health in migrants has been studied from various perspectives within different healthcare systems (Laue et al., 2023, p. 381). Organizations such as the World Health Organization (2019) have also promoted health in migrants and refugees.

However, a significant portion of existing research focuses on the mental health of migrants, while less attention has been paid to physical health specifically. Some studies, such as that by Martin and Sashidharan (2023, p. 427), address mental health in migrants and other aspects related to psychological issues stemming from the migration process (Brunnet et al., 2020. P. 364). Furthermore, negative health effects related to the process of acculturation have been identified (González, 2022, p. 758), underscoring the importance of considering migration as a social determinant of health (Vélez et al. 2013, p. 156; Martínez, 2022, p. 72).

These determinants are often linked to the disparities in access to healthcare systems faced by migrant populations compared to the native population. In the case of Spain, the increase in the migrant population in the 2000s led to the implementation of governmental measures that transformed the universal healthcare system into an insured healthcare system. With the enactment of Decree Law 16/2021, dated April 20, healthcare coverage was limited to individuals within the labor or legal system. Consequently, migrants without residency permits were excluded from the healthcare system except in some extreme cases. Subsequently, in 2018, Decree Law 7/2018, dated July 27, partially reinstated a Universal Access Healthcare System (Muñoz, 2022, p. 1). These actions created a gap in healthcare access between native and migrant populations in Spain, which still persists to this day (Antón and Muñoz, 2010, p. 489; Suárez, 2022, p. 1). Similarly, at the European level, disparities between the health of migrant and native populations are identified, whether in positive aspects (Maskileyson, 2019) or negative ones (Jiang, 2023, p. 184). European social policies and factors associated with migration are significant differentiators in the health of natives and migrants (Reus-Pons, 2018, p. 5).

It's worth noting that research on migration and disability is scarce and specific. One of the main references in the Spanish context is the report by Díaz et al. (2008, p. 17), which has stood out for its contribution to the study of migrants with disabilities both quantitatively and qualitatively.

This sub-topic is considered essential when investigating the health of migrant individuals, as both disability and health are fundamental aspects in the life cycle (World Health Organization, 2023). In many cases, the migration process itself can trigger one or more disabilities, as evidenced in studies by Couldrey and Herson (2010, p. 1).

To counteract these circumstances, it is important to identify that migrant individuals possess protective factors and resilience within migrant communities, which represent a significant social capital. These communities uphold cultural norms and support networks as sociosanitary protection factors. Authors such as Mateo (2005, p. 194) or Célleri and Jüssen (2012, p. 147) recognize social capital as a means of migrant integration, with ethnic solidarity serving as a protective factor. This implies that migrant communities employ strategies in response to the impacts of migration, which are coped with through social support. Aspects that highlight the importance of taking into account social support in migrants as a determining factor of their health both in the current study and in future ones.

In this theoretical context, and after an exhaustive scientific review, the need to investigate and understand the perception that migrant individuals in Spain have regarding their physical health from a qualitative perspective has been identified as a research problem. Additionally, it's important to identify the main sociodemographic characteristics of this population in order to define homogeneous profiles.

Therefore, this study has the following main objectives: I) To find out the perception that migrants participating in this study have of their health, including aspects related to physical health, disability and access to health services; II) To identify and describe the main characteristics of the migrant population participating in the study, focusing on the socio-demographic data that define their profiles.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The methodology employed for conducting this study is qualitative and based on a critical theory approach (Guba and Lincoln, 2002, p. 113). A method known as Grounded Theory is utilized, allowing the identification of fundamental social processes and the development of theory from the obtained data (Hernández-Sampieri and Mendoza, 2020, p. 235). The application of this methodology involves three essential phases: introduction, deduction, and verification.

In the introduction phase, a theoretical construct is identified and established through a thorough review of prior research and an analysis of the current state of the art that frames the study's phenomenon. In the deduction phase, primary information obtained is analyzed, categories defining subsequent analysis are designed, and relationships among them are established. Finally, in the verification phase, data collected during fieldwork are compared with the initial theoretical construct, thus generating the study's results.

To ensure research quality and the correct application of qualitative methodology, the guidelines proposed by O'Brien et al., (2014, p. 1245) were followed, which establish 21 minimum items for ensuring the quality of qualitative studies.

2.1. Participants and Context

The study involved 135 individuals residing in various locations in Spain. Among the participants, 52 were women, and 83 were men, ranging in age from 18 to 70 years. Their common characteristic was their migrant status, a fundamental requirement for participation in the study. The sample exhibited great heterogeneity in terms of nationalities (up to 32 nationalities represented) and legal statuses (asylum seekers, settled migrants, etc.).

Participant selection utilized convenience non-probabilistic sampling and the snowball method. The process of accessing the sample began by contacting third-sector institutions, requesting their collaboration in the research. Those institutions that responded positively allowed interviews with migrant individuals to be conducted at their premises. In the cities where the study was carried out, primarily in Madrid, the Valencian Community, Murcia, Castilla-La Mancha, and Andalusia, access to the sample was similar. However, the snowball method often led to the possibility of conducting additional interviews after a group interview. In Andalusian cities, researchers accessed collaborating entities to recruit new participants. In other cities (such as Madrid, Murcia, etc.), researchers, in addition to accessing the sample through institutions, arranged direct appointments through previously interviewed participants. The selection of these locations was based on the willingness of participants to collaborate in the research. It is important to note that the collaboration of some institutions/NGOs was limited due to the humanitarian crisis resulting from the conflict between Ukraine and Russia.

The principle of saturation determined the cessation of including new participants, as group interviews provided abundant information on the study topic without new information emerging in subsequent stages.

2.2. Instruments

Several typical instruments of qualitative research were employed to collect data. The researchers themselves acted as interviewers and observers, given their backgrounds in Social Work. The primary instrument was the semi-structured group interview and individual sociodemographic data sheet. Group interviews were chosen to leverage the presence of companions and increase the sample size and data simultaneously. Brief questions were designed to ensure equitable participation among all present during interviews.

The interview consisted of three open-ended questions addressing health, illnesses, disabilities, and access to healthcare resources. Additionally, sociodemographic data were collected through a self-administered individual data sheet containing nine closed-ended questions concerning gender, age, country of birth, marital status, pre-migration employment status, educational level, and reasons for migration.

In addition to these instruments, a voice recorder and interview guide were used to adequately document the data.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted following established ethical standards and protocols for research involving human subjects at the university where it took place. Approval for the study was obtained from the respective Ethics Committee. Information was provided, and informed consent was obtained from the participants, with particular emphasis on compliance with the Organic Law 3/2018 on Data Protection and Digital Rights Guarantee. Additionally, this study adheres to the ethical considerations of the American Psychological Association (2017).

2.4. Procedure and Analysis Plan

Data collection took place during the months of January, February, March, and April of the year 2023. This involved conducting 18 group interviews with 7 to 8 participants in each interview, lasting 40-60 minutes. The key phases that shaped the fieldwork and data analysis are:

Documentary analysis phase: In this phase, a documentary search is conducted to establish the foundations of the study object. The Web of Science, Scopus, and Pubmed databases are utilized for this purpose. Additionally, the bibliographic management tool RefWorks is employed to select the most relevant theoretical sources and eliminate those that do not correspond to the studied phenomenon. This initial search and analysis contribute to composing the theoretical framework of the study.

Qualitative data collection phase: To initiate the fieldwork phase, contacts were established with third-sector institutions dedicated to working with migrant populations. The collaborating institutions were presented with documents approved by the Ethics Committee of the respective university. Through these institutional contacts, the researchers gained access to the study sample. Initially, an interview script and sociodemographic data sheet were designed.

Data Analysis Phase: In this stage, the collected data from the group interviews undergo scrutiny. Recordings are transcribed, with codes assigned (alternate arrangement of last names + participation order) to ensure the anonymity of participants. Following transcription, Atlas.ti Version 22 (Thomas Muhr, 2002) is employed as a tool for qualitative data analysis.

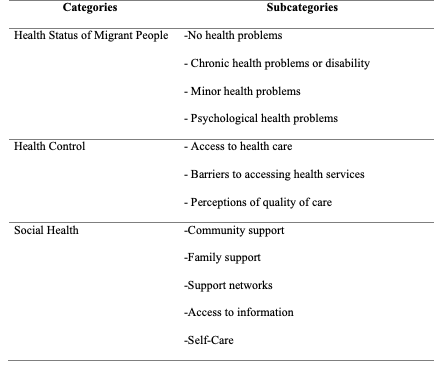

The data analysis is broken down into three phases: general and open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Categories were crafted based on interactions within the main categories "Health Status of Migrant Individuals," "Health Control," and "Social Health." These categories were further subdivided into subcategories (see Table 1) to identify patterns in the data and develop a theory based on them.

Tabla1, Categories and subcategories of analysis

Source: Own elaboration

Finally, for the analysis of sociodemographic results, given their quantitative nature, excel software (2010) was utilized to code and process data from individual sociodemographic sheets. This involved identifying the frequency and percentage of responses for each item.

3. RESULTS

The findings of this research are divided into four sections. Firstly, there's the block of data and sociodemographic characteristics of migrant individuals. These data allow for the definition of specific profiles of the migrant population in Spain and provide insight into their previous and current situations before migration.

Secondly, the discoveries regarding health in migrant individuals are highlighted, focusing on whether they suffer from any illnesses. This includes the types of illnesses they experience. Thirdly, the findings on health control and access to the healthcare system are presented. Lastly, the results on social support are outlined. These outcomes are derived through the analysis of categories and the descriptive interpretation of the narratives.

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of migrant individuals

The findings of this research are divided into two categories. Firstly, we present the data and sociodemographic characteristics of the migrant population. These data help define some typical profiles of migrant individuals in Spain and provide information about their situation both before and after migration. Secondly, we describe the results related to the health of this population, focusing on the presence of diseases, the types of diseases suffered, and the control of their health. All of this is achieved through category analysis and descriptive interpretation of testimonies.

Regarding sociodemographic data, the main characteristics of the migrant population and their situation before and after migration are highlighted. The elements considered for organizing and analyzing this data include age, gender, place of birth, reasons for migration, previous employment status, marital status, and educational level achieved.

In terms of age, the studied population includes individuals aged 18 to 70, with a higher number of those between 18 and 28 who are employed. Regarding gender, there is a higher participation of men (61.48%) compared to women (38.52%). Concerning place of birth, up to 32 different nationalities were identified. According to the established categories, 61.5% come from African countries (such as Morocco, Mali, Senegal, Algeria, Sudan, Cameroon, among others), followed by 23.7% from South America (Colombia, Ecuador, Cuba, Venezuela, El Salvador, etc.). 7.4% come from European countries like Romania, Poland, Ukraine, and Estonia, while 5.9% originate from Asia (Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Palestine, and Afghanistan). Lastly, 1.5% come from Eurasia, primarily from Russia. These data reflect the rich cultural and social diversity of the migrant population in Spain.

The reasons for migration show that 44% of individuals mentioned labor, economic, or study-related reasons as the primary motive for their migration. 38% indicated that their migration was due to armed conflicts or persecutions based on ideology, gender, among others. Finally, 19% identified reasons related to health and family reunification. These results underscore how the geopolitical situation in the country of origin can influence migration motives.

It is relevant to observe the relationship between migration motives and gender. 20% of women migrated for labor, economic, or study-related reasons, while 11% did so due to armed conflicts, violence, or persecution, with gender-based violence and sexual orientation persecution being prominent in this group. On the other hand, 7% of women mentioned reasons related to health and family reunification. In the case of men, 24% migrated for economic, labor, or study-related reasons, while 27% did so due to armed conflicts and persecutions. 11% of men mentioned reasons related to health or family reunification. Despite the disproportionate number of participants of each gender, the figures for migration due to labor, economic, etc., reasons remain similar, highlighting the persistence of female labor migration over time.

Another noteworthy aspect is the employment status before migration, as it is one of the main factors influencing the decision to migrate. The data reveal that 39% of people were employed before migration, while 30% were studying at various educational levels. In third place were those who were unemployed (24%), followed by those engaged in domestic work (5%). Those who were retired before migration were in the last position (1%). These data indicate that 59% of participants were unemployed or engaged in other activities before migration, explaining the high number of migrations for labor, economic, and study-related reasons.

Regarding marital status, it is observed that 44% of people are single, followed by 30% who are married. Only 16% have a partner, while 5% are widowed, and 4% are separated or divorced. These data show that the majority of migrant individuals do not have a close nuclear family to provide a minimal support system.

Regarding the level of education achieved, the results indicate that 72% of individuals do not have higher education. Of this group, 26% have completed secondary education, while 24% have reached primary education, and 15% have vocational training. Additionally, 7% of migrant individuals stated that they did not attend any educational institution. From these data, only 28% have university education. These results demonstrate a close relationship between the level of education and migration motives.

In summary, the results provide a general overview of the profiles and characteristics of the migrant population residing in Spain today. In addition to the highlighted profiles, it is important to consider the diversity of profiles that can be extracted from the data, emphasizing the heterogeneity of this population.

3.2. Health status of migrant individuals

3.2.1. Health among migrant individuals

In response to the health dimension in migrant individuals, a category of "health satisfaction" is introduced. Most of the participating people express their satisfaction with their health based on their current situation. In most cases, this satisfaction is described as normal or good. It is identified that health is a fundamental aspect of life, without which a good quality of life cannot be established. Many people relate basic daily life needs to good health, assigning health a value equivalent to life itself. Furthermore, working conditions and nutrition are associated with improved health, leading to connections between both the pre-migration and current situations with improved health.

On the other hand, some participants identify their perception of health as very good, indicating a higher emphasis on the importance of health. However, in these perceptions, there is an underlying relationship between health and life experiences. Specifically, there is a tendency to highlight situations where health is affected by adverse circumstances such as war, persecution, violence, or migration itself. Data is obtained that emphasises gender-based violence as a reason for initiating migration, providing deeper qualitative insight into this reality. It is observed that, in comparison to previous situations, satisfaction with health has significantly increased. However, it is essential to consider that all situations of vulnerability or adversity can lead to poor health or, therefore, low satisfaction with it. The biographical significance of these results is shown in the narratives:

I feel fine with my health; I'm young and have no illnesses, but it's essential to be surrounded by a good environment to stay well. If things are going poorly in your context, you don't have health, even if you have it. (ZP106)

Migrating to improve health is common; without health, you wouldn't be alive, and family makes it better. I'm thankful for what I have, and that's why I'm very satisfied with my health right now. (NP7)

Without food or work, there is no health, so leaving to find food makes health much better. Health is the ability to work. (DP121)

In this regard, there is frequent mention of the value of psychological or emotional health. In many cases, when discussing health, there is a direct connection with the migration process, such as in the case of war or an adverse context. A direct link is established between the current state of health and the peace of mind from having migrated to a country with better living conditions. Additionally, the spiritual and metaphysical aspects of religion are addressed, where life's tranquillity is linked to good mental health. Some testimonies exemplify this idea:

It's very important to be well, not just physically, but also in terms of the soul because the body is almost always fine, but the soul can be wounded and needs healing. Although it's not like before, that's why I believe I'm satisfied... like everyone else, normal. (JP2)

In summary, overall, the participants generally agree that it's crucial to have a supportive environment to maintain good health. These findings, along with age-related data, could indicate that the migrant population falls within an age range where health is still good or moderately good.

3.2.2. Health issues in the migrant population

Another central category in the study relates to health issues in the migrant population. From this category, four analytical subcategories are derived, forming the result blocks: 1) Absence of health problems; 2) Chronic health problems or disabilities; 3) Mild health issues; 4) Psychological health problems.

3.2.3. Non-existence of health problems

Addressing issues related to the existence of health problems sometimes implies finding data that suggests their non-existence as a result. This means that in the study, a significant proportion of participants in the interviews coincided in not suffering from any diseases or health problems affecting their lives. Some of the health problems they suffer from have not been diagnosed, making them unable to be identified as actual health problems. In some cases, the ailments they suffer from are associated with other types of experiences that are not considered health problems. These testimonies reflect the perspective of some individuals:

So, I don't have any health problems. Although sometimes I experience pain due to work, but I don't consider them illnesses. (MP45)

No, I left because my sexual orientation and gender are considered an illness in my country, but I don't believe I have an illness. This is how I was born, and I don't harm anyone with my life. (KP13)

Even though my back hurts sometimes, it's not important. I'm a hardworking man, and I've been working for many years. I don't have illnesses. (AP62)

3.2.4. Chronic health problems or disabilities

The identification of health problems begins with participants who have chronic health problems and, in some cases, disabilities. Overall, these conditions are addressed positively, with individuals stating that they are not impediments to living a normal life. Social participation is emphasized as an important aspect and is related to the establishment of social networks and interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, it is recognized that maintaining some of these social networks can be beneficial for managing these diseases. It is emphasized that it is essential to positively incorporate illness or disability into daily life, which implies not feeling excluded from society. These testimonies are illustrative:

I have diabetes, but it's not a problem. I can eat well and lead a normal life. I've even met people with my same condition here, and we share our experiences. (BP86)

I have been blind for many years, but that doesn't stop me from doing things. I've learned to navigate the city and lead a normal life. I even have friends here who help me if needed. (FP35)

My sister has a disability, but she has always been a part of our family, and we don't exclude her from anything. She has found good support here and has improved her quality of life. (LP127)

3.2.5. Mild health problems

Regarding mild health problems, the collected data show that they are relatively common in the migrant population but are generally considered manageable and not severe. These problems can include conditions such as colds, allergies, headaches, and other temporary physical discomforts. Interview participants tend to downplay these problems and consider them part of everyday life. Most of the time, these health problems are treated with home remedies or over-the-counter medications. Some testimonies exemplify this perspective:

From time to time, I catch a cold, but it's not a big deal. I take some medicine and recover quickly. (EP98)

I get headaches often due to stress and work, but it's not a serious issue. I just take something for the pain, and I'm fine. (HP34)

I have allergies sometimes, especially in spring, but it's not a major problem. I simply avoid what triggers my allergies, and I feel better. (PP115)

3.2.6. Psychological health problems

The category of "psychological health problems" refers to mental and emotional conditions faced by the migrant population. These problems can result from previous traumas, challenging migration experiences, or the stresses associated with adapting to a new cultural and social environment. Mental health problems are considered a significant concern, and many interviewees have experienced symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Often, the lack of access to adequate mental health services is mentioned as a challenge in addressing these problems. Some testimonies reflect these experiences:

The war in my country left many invisible wounds. Sometimes, I feel overwhelmed by anxiety and bad memories. I don't know where to turn for help here. (IP8)

Loneliness and nostalgia are hard to manage. I miss my family and my country, and it makes me feel sad most of the time. But I try to stay strong. (UP46)

Adapting to a new culture can be stressful. Sometimes, I feel like a stranger in a strange place, and it affects me emotionally. (XP101)

In summary, this category reveals that psychological health problems are a significant concern in the migrant population. The lack of support and adequate mental health services can be a barrier to addressing these problems effectively.

3.3. Access to health services in the host country

The third central category of the study deals with access to healthcare services in the host country. From this category, results are derived that pertain to: 1) Access to healthcare; 2) Barriers to accessing healthcare services; 3) and the perception of the quality of healthcare in the host country.

3.3.1. Access to medical care

In general, the majority of interviewed migrant individuals report having had access to healthcare services in their host country. This is largely attributed to universal healthcare policies or specific programs for migrants in some receiving countries. Medical care is typically accessible in terms of geographical location and service availability. Moreover, many migrant individuals emphasize the importance of having health insurance or a medical care card that allows them to access care without prohibitive costs. Some testimonies reflect this perspective:

Here in the host country, I have no problems seeing a doctor. I just present my health insurance card, and I receive treatment without any issues. (KP104)

The healthcare system here is excellent. I can receive quality medical care without worrying about costs. (WP107)

I have a chronic medical condition, and the healthcare system here has been very helpful. I don't have to wait long to see a specialist. (LP105)

3.3.2. Barriers to accessing health services

Despite widespread access to medical care, some participants mention obstacles they have encountered when seeking medical attention in their host country. These obstacles may include language barriers, lack of familiarity with the local healthcare system, discrimination by medical personnel, and difficulties in finding a healthcare provider who understands their specific cultural and medical needs. Some testimonies illustrate these challenges:

Sometimes it's hard to communicate with doctors due to the language. Interpreters are not always available, and that makes healthcare difficult. (JP119)

I've felt that some doctors don't understand my culture and my beliefs about health very well. This can lead to misunderstandings in treatment. (CP10)

Overall, I've had good experiences with the healthcare system here, but I know that other migrant individuals have faced discrimination in hospitals. (HP6C)

3.3.3. Perception of the medical care

The perception of the quality of medical care varies among interviewees. Some migrant individuals have a positive opinion of healthcare in their host country and consider it of high quality. Others have criticisms and believe that healthcare could improve in terms of accessibility, waiting times, and cultural sensitivity. The perception of the quality of medical care often relates to individuals' personal experiences and can vary depending on the region and the specific healthcare system of the host country. Some testimonies reflect these perspectives:

I'm very satisfied with medical care here. I'm always treated with respect, and I feel well cared for. (NP29)

Medical care is good, but I feel they could improve in terms of waiting times. Sometimes, you have to wait a long time to get an appointment. (UP120)

I've had both good and bad experiences with doctors here. Some are very kind and understanding, while others can be insensitive. (RP13)

In summary, the perception of the quality of medical care varies among migrant individuals, but generally, the majority report having access to healthcare services in their host country. However, there are obstacles and challenges that can affect each individual's healthcare experience.

3.4. Coping strategies and social support

The fourth central category of the study focuses on the "coping strategies and social support" used by the migrant population to deal with health issues and barriers in accessing healthcare. This category includes subcategories related to community support, family support, support networks, seeking information, and self-care.

3.4.1. Community support

Community support plays a significant role in the lives of many migrant individuals. Some participants mention feeling supported by their communities of origin or by migrant communities in the host country. This support can manifest through local organizations, cultural groups, places of worship, and social events that help create a sense of belonging and provide emotional support. Some testimonies illustrate this perspective:

My church has been an important source of support for me. I've met many people who have gone through similar experiences, and we support each other. (BP108)

We gather with other migrants from our country every week. It's comforting to be with people who understand our experiences and challenges. (GP131)

We have a tight-knit community here. We help each other in tough times, whether it's sharing information about healthcare services or providing emotional support. (SP112)

3.4.2. Family support

Family support is a fundamental source of support for many migrant individuals. Family plays a crucial role in adapting to a new environment and managing health problems. This includes emotional support, assistance in navigating the healthcare system, and, in some cases, financial support to cover medical expenses. Some testimonies highlight the importance of family support:

My family is my primary support. They take care of me when I'm sick and accompany me to medical appointments if necessary. (UP85)

I know I can always count on my family. They help me stay strong and give me advice on how to take care of my health. (WP31)

My family sends me money when I have medical expenses. Knowing that you have that support is reassuring. (CP58)

3.4.3. Support networks

In addition to community and family support, some migrant individuals mention that they have established support networks in the host country. These networks can include close friends, coworkers, neighbors, and other contacts who provide help and support in various situations, including those related to health. Some testimonies reflect this perspective:

My friends here are like a second family. They're always willing to help me, whether it's taking me to the doctor or just listening when I need to vent. (BP28)

I have a group of friends at work, and we all support each other. If one of us gets sick, the others are there to help. (OP17)

My neighbors are very kind. They're always willing to help us if we need anything, whether it's with the kids or in medical emergencies. (MP11)

3.4.4. Seeking information

Information-seeking is a common strategy used by migrant individuals to gather information about healthcare in the host country. This may include online research about healthcare providers, migrant healthcare rights, health insurance options, and other health-related resources. Some participants emphasize the importance of being well-informed to make informed decisions about their healthcare. Some testimonies illustrate this perspective:

I always research online before scheduling a medical appointment. I want to make sure I'm going to the right place and have all the necessary documents. (KP1)

Online information has helped me better understand how the healthcare system works here and what my rights are as a migrant. (RP22)

We share useful information among ourselves, like which hospitals are good and where you can get free medical care if you need it. (IP135)

3.4.5. Self-care

Self-care is an important strategy for maintaining health and preventing health problems in the migrant population. This includes healthy lifestyle habits such as a balanced diet, regular exercise, adequate rest, and stress management. Some migrant individuals emphasize the importance of taking care of themselves and taking preventive measures to maintain their health. Some testimonies reflect this perspective:

I try to maintain a healthy diet and exercise regularly. I want to be in good physical and mental shape. (FP92)

Stress can significantly affect health, so I practice meditation and relaxation to stay calm. (NP3)

Prevention is key. I do everything I can to avoid illnesses, like getting vaccinated and having regular check-ups. (ZP41)

In summary, coping strategies and social support play a crucial role in the lives of migrant individuals in dealing with health issues and barriers in accessing healthcare. These strategies include community support, family support, support networks, information-seeking, and self-care.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the amount of research focused on the health of migrant populations. This reflects a growing recognition of the need to address the physical health of this specific group of people (Díaz et al., 2019, p. 73). The impact of the migration process on people's health is a reality that requires attention from both the scientific community and different states. Furthermore, it is essential to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of migrant individuals, as these personal characteristics play a fundamental role in the social determinants of health (Solar and Irwin, 2007, p. 54; Piñones-Rivera et al., 2021, p. 2; Muñoz, 2022, p. 1).

Aspects such as migration motives, gender, country of origin, marital status, and employment status are relevant factors in this context (Aguilera et al., 2020, p. 16). These elements, which are also addressed in the present study, are identified by authors like Vertovec (2007, p. 1024) as components of superdiversity. This concept refers to the diversity of individuals beyond their ethnicity or migration status and recognizes diversity as a social value (Martín-Cano, 2020).

Previous research, like this study, has highlighted the importance of having data that allows the identification of characteristics defining the situation of migrant populations (Mena y Cruz, 2018, p. 270). This is crucial for developing effective policies and actions in response to migration trends (Martínez, 2005, p. 7; Krzesni and Brewington, 2022 p. 4), especially in the field of social health policies, with the aim of avoiding situations like those experienced during the 2015 refugee crisis. These situations served as a precedent for current events, such as the humanitarian crisis resulting from the conflict between Ukraine and Russia (Arenas, 2022, p. 11).

In the second part of the results, a discourse is evident in which participants express their perception of health and the control they have over it (Torres, 2022, p. 19). This influences their satisfaction with health, the presence of physical health problems (chronic or mild), psychological issues, and the relationship between health and migration. One of the most relevant findings is the presence of various chronic pathologies in the migrant population and their relationship with migration motives, results related to research by authors such as Mesa-Vieira et al. (2023, p. 469) and Vearey (2023). However, it is important to note that there is a shortage of theoretical production addressing physical pathologies and disabilities in migrant individuals. One of the few theoretical references that addresses disabilities, as in this study, is the report proposed by the Spanish Committee of Representatives of Persons with Disabilities (CERMI) (Díaz et al., 2008, p. 17). Therefore, it is essential to provide data on the phenomenon of physical health in migrants.

Regarding the presence of psychological problems such as anxiety or depression, numerous studies confirm this reality in the migrant population, as shown in this study (Carrol et al., 2023, p. 279). This is due to the vulnerability experienced during the migration process and acculturation (Trilesnik et al., 2023, p. 289), highlighting the importance of considering the migration situation as a social determinant of health (Van der Laat, 2017, p. 15).

Another important finding in the second part of the results pertains to access to the healthcare system. The results indicate that, similar to findings in studies such as Llop-Gironés et al., (2014, p. 722), migrant individuals utilizing the healthcare system perceive the healthcare system of the host country as an opportunity to care for their health without worrying about costs.

Similarly, there are findings indicating the limited use of the healthcare system for health monitoring or treatment due to the barriers associated with migration. This contrasts with data provided by studies like those of Cabises et al. (2012, p. 3) or Buchcik et al. (2021, p. 1), which demonstrate that access to the healthcare system by migrant populations is consistently more limited compared to the native population.

This may be due to cultural barriers or a lack of awareness about healthcare rights. In this regard, authors such as Chen et al. (2004, p. 1984) identify human resources for health as a challenge to be addressed by states and societies in terms of social inclusion.

Finally, the study provides results on perceived social support among the migrant population, aligning with studies such as Hernández et al., (2004, p. 83) or Sosa and Zubieta (2015, p. 38), which identify the difficulty in establishing new support networks in the host country. However, migrant communities serve as both social and ethnic capital where individuals find protection and support (Mateo, 2005).

In summary, this research adds to the broader understanding of health in migrant individuals, taking into account their physical, psychological, and social aspects in relation to their personal characteristics. Therefore, a key takeaway is the necessity for an expanded exploration of the physical health of migrants, from a social standpoint. A qualitative examination of health concerning the experience of physical pathologies and disabilities in migrant individuals is crucial as a groundwork for effectively designing interventions that address the genuine needs of the migrant population in socio-sanitary terms in the future.

Lastly, it's crucial to emphasize the significance of health in migrant individuals as a means to extend healthcare rights to the entire population indiscriminately. The findings indicate a clear lack of healthcare protection for migrant individuals. This study not only provides theory supporting the professional practice of social work regarding exploring the health of migrants but also raises awareness among healthcare professionals. In other words, this qualitative study yields results that help identify social needs and barriers that hinder the exercise of the Right to Health within the healthcare system.

Therefore, the findings enable the visibility of the phenomenon of migrant individuals and their health from a social perspective, serving as a foundation for both Social Work and healthcare personnel involved in migrant health care.

Before concluding, it is important to highlight some limitations of this study. Challenges in researching with migrants lie in the difficulty of accessing the sample. The circumstances surrounding migration make it complicated to recruit migrant participants, and at times, establishing trust bonds with them and ensuring their participation in the study can be difficult.

Consequently, the sample ends up being limited, and the results are extrapolatable only to a certain extent based on the sample size. Additionally, the role of institutions in accessing the sample limits the study's extension to other cities in Spain. Another significant limitation is the scarcity of studies on migrant health from the realm of social sciences, which constrains the development of an extensive theoretical framework. However, these limitations morph into opportunities to maintain the research line as a priority, given the necessity of providing scientific theory to the social phenomenon of migrant health.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the brave and generous individuals who participated in this study, hailing from various nationalities and residing in Spain. Their active participation and honesty have significantly enriched our understanding of the experiences and challenges they face in their daily lives. The diversity of perspectives and life experiences shared by each participant has been crucial to the depth and breadth of our findings. We are deeply grateful for their time, dedication, and the valuable contribution they have made to this research. The rest of the acknowledgments will be included in the manuscript after acceptance, to maintain anonymity.

6. REFERENCES

Aguilera, Y. O., Hernández, N. N., Pincheira, L. S. y Urbina, A. C. (2020). Caracterización de la migración y los determinantes sociales de la salud en el Continente Americano. Applied Sciences in Dentistry, 1, 16-7. https://doi.org/10.22370/asd.2020.1.0.2603

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. APA. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Antón, J. I. & Muñoz, R. (2010). Health care utilisation and immigration in Spain. The European Journal of Health Economics, 11(5), 487-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-009-0204-z

Arenas, M. D. L. M. L. (2022). Crisis humanitaria en Ucrania: Acción europea en el marco de la directiva 2001/55/ce del consejo y otras cuestiones relacionadas. Cuadernos Cantabria Europa, 21, 11-33. https://onx.la/04d7b

Bozorgmehr, K., Kühne, S. & Biddle, L. (2023). Local political climate and spill-over effects on refugee and migrant health: a conceptual framework and call to advance the evidence. BMJ Global Health, 8(3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011472

Brunnet, A. E., Dos Santos, N., Silveira, T., Kristensen, C. H., & Derivois, D. (2020). Migrations, trauma and mental health: A literature update on psychological assessment. L’Encéphale, 46(5), 364-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2020.03.009

Buchcik, J., Borutta, J., Nickel, S., Knesebeck, O. & Westenhöfer, J. (2021). Health-related quality of life among migrants and natives in Hamburg, Germany: An observational study. Journal of Migration and Health, 3(100045), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100045

Cabises, B., Tunstall, H., Pickett, K. & Gideon, J. (2012). Understanding differences in access and use of healthcare between international immigrants to Chile and the Chilean-born: A repeated cross-sectional population-based study in Chile. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11(68), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-68

Carroll, H. A., Kvietok, A., Pauschardt, J., Freier, L. F. & Bird, M. (2023). Prevalencia de trastornos de salud mental comunes en poblaciones desplazadas por la fuerza frente a los migrantes laborales por fase de migración: un metanálisis. Revista de Trastornos Afectivos, 321, 279-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.010

Célleri, D. & Jüssen, L. (2012). Solidaridad étnica y capital social. El caso de los comerciantes migrantes kichwa-otavalo en Madrid y La Compañía. Procesos. Revista Ecuatoriana De Historia, 36, 143–168. https://doi.org/ 10.29078/rp.v0i36.33

Chen, L., Evans, T., Anand, S., Boufford, J. I., Brown, H., Chowdhury, M. & Wibulpolprasert, S. (2004). Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. The lancet, 364(9449), 1984-1990. http://www.healthgap.org/ camp/hcw_docs/JLI_exec_summary.pdf

Couldrey, M. y Herson, M. (2010). Discapacidad y Desplazamiento. Migraciones Forzadas revista, 35, 1-60. https://n9.cl/f1dax

Díaz, E., Huete, A., Huete, M. A. y Jiménez, A. (2008). Las personas migrantes con discapacidad en España. Madrid, Observatorio Permanente de la Migración y CERMI. https://onx.la/71231

Díaz, R. M., De la Fuente, Y. M. y Muñoz, R. (2019). Migraciones y diversidad funcional. La realidad invisible de las mujeres. Collectivus, Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 6 (1), 61-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.15648/Coll.1.2019.5

González, S. (2022). Estrés por aculturación y salud mental en migrantes en Latinoamericanos una revisión del estado del arte del 2010-2021. Colombia, Universidad Católica de Pereira.

Guba, E., y Lincoln, Y. (2002). Paradigmas en competencia en la investigación cualitativa. En Derman, C. y Haro, J. (Comps.) Por los rincones. Antología de métodos cualitativos en la investigación social (pp. 113-145). México, La Sonora: El Colegio Sonora.

Guerrero, P., y Pérez, A. R. (2023). Organizaciones y migración, complejidad y sistemas dinámicos. Política y Cultura, 59, 235-255. https://doi.org/10.24275/UACT5337

Hernández, S., Pozo, C. y Alonso, E. (2004). Apoyo social y bienestar subjetivo en un colectivo de inmigrantes, ¿efectos directos o amortiguadores? Boletín de psicología, 80(80), 79-96.

Hernández-Sampieri, R. y Mendoza, C. P. (2020). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. Argentina, MCGRAW-HILL.

International Organization for Migration. (2019). Derecho internacional sobre migración: Glosario de la OIM sobre migración. ONU Migración. Disponible https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml-34-glossary-es.pdf.(20 enero 2023).

International Organization for Migration. (2023). Informe sobre las Migraciones en el Mundo 2022. OIM. https://onx.la/3fe4d

Jiang, J. (2023). Relationship between social cohesion and basic public health services utilisation among Chinese internal migrants: a perspective of socioeconomic status differentiation. Health Sociology Review, 32(2), 179-197.

Jiménez, C. y Tprin, V. (2023). Pensar las migraciones contemporáneas. Categorías críticas para su abordaje. Córdoba, Teseopress.

Krzesni, D., and Brewington, L. (2022). Climate change, health, and migration: profiles of resilience and vulnerability in the Marshall Islands. Honolulu, East-West Center.

Laue, J., Diaz, E., Eriksen, L. & Risør, T. (2023). Migration health research in Norway: a scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 51(3), 381-390. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211032494

Lee, E. S. (1966). A Theory of Migration. Demography, 3(1), 47-57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060063

Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 294, de 06/12/2018. https://boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2018-16673&tn=2

Llop-Gironés, A., Vargas Lorenzo, I., Garcia-Subirats, I., Aller, M. B., y Vázquez Navarrete, M. L. (2014). Acceso a los servicios de salud de la población inmigrante en España. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 88, 715-734.

Martín-Cano, M. d. C., Sampedro-Palacios, C. B., Ricoy-Cano, A. J. & De La Fuente-Robles, Y. M. (2020). Superdiversity and Disability: Social Changes for the Cohesion of Migrations in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186460

Martin, F. & Sashidharan, S. P. (2023). The mental health of adult irregular migrants to Europe: a systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 25(2), 427-435.

Martínez, C. (2005). Perfil sociodemográfico de la población migrante en Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. Migración internacional, el impacto y las tendencias de las remesas en Colombia. Colombia, OIM.

Martínez, H. A. (2022). ¿Simplificación o reducción? ¿Complejidad? La perspectiva crítica de la Salud Colectiva sobre los determinantes sociales de la salud. Salud Problema,14(29), 72-87. https://n9.cl/bxuq0

Maskileyson, D., Semyonov, M. & Davidov, E. (2019). In Search of the Healthy Immigrant Effect in Four West European Countries. Social Inclusion, 7(4), 304-319. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i4.2330

Mateo, A. E. (2005). Las redes sociales y el capital social como una herramienta importante para la integración de los inmigrantes. Acciones e investigaciones sociales, 21, 185-204.

Microsoft Excel. (2010). Microsoft Office Versión 2010 [Software]

Muñoz, J. S. (2022). Brecha de uso de la atención sanitaria entre la población autóctona e inmigrante en España. Migraciones. Publicación del Instituto Universitario de Estudios sobre Migraciones, 56, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.14422/mig.2022.016

Mena, L. y Cruz, R. (2018). Migrantes retornados de España y los Estados Unidos: Perfiles y situación laboral en Ecuador. RIEM. Revista internacional de estudios migratorios, 7(4), 270-302. https://doi.org/10.25115/riem.v7i4.1968

Mesa-Vieira, C., Haas, A. D., Buitrago-Garcia, D., Roa-Diaz, Z. M., Minder, B., Gamba, M. & Franco, O. H. (2022). Mental health of migrants with pre-migration exposure to armed conflict: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 7(5), 469-481.

National Institute of Statistics. (2022). Cifras de Población (CP) 1 de julio de 2022. Primer semestre 2022 [Conjunto de datos]. INE. https://ine.es/prensa/cp_j2022_p.pdf.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A. & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245-1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2023). Flujos migratorios en países de la OCEDE. Publicaciones. Mejores políticas para una vida mejor. Disponible en http://www.oecd.org/espanol/publicaciones /migracion.htm. (3 febrero 2023).

Piñones-Rivera, C., Concha, N. L. y Gómez, S. L. (2021). Perspectivas teóricas sobre salud y migración: Determinantes sociales, transnacionalismo y vulnerabilidad estructural. Saúde e Sociedade, 30(1), 2-18. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902021200310

Reus-Pons, M., Mulder, C. H., Kibele, E. U., and Janssen, F. (2018). Differences in the health transition patterns of migrants and non-migrants aged 50 and older in southern and western Europe (2004–2015). BMC medicine, 16, 1-15.

Solar O. and Irwin A. (2007). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Discussion paper for the commission on social determinants of health. Geneva, World Health Organization. Disponnible http://en.scientificcommons.org/23007732. (13 febrero de 2023).

Sosa, F. y Zubieta, E. (2015). La experiencia de migración y adaptación sociocultural: identidad, contacto y apoyo social en estudiantes universitarios migrantes. Psicogente, 18(33), 36-51.

Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid. (2023). Situación de los refugiados en España [Conjunto de datos]. CEAR. https://www.cear.es/situacion-refugiados/

Suárez, J. (2022). Brecha de uso de la atención sanitaria entre población autóctona e inmigrante en España. Migraciones. Publicación del Instituto Universitario de Estudios sobre Migraciones, 56, 1-23. http://doi.org/10.14422/mig.2022.016

Torres, M. (2022). Caracterización socio-demográfica y laboral de los inmigrantes latinoamericanos, calificados y no calificados, residentes en México y España. Entorno Geográfico, 23, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.25100/eg.v0i23.11706

Thomas Muhr. (2002). Sciendific Software Development GmbH. Atlas.ti 22 Mac [Software]

Trilesnik, B., Stompe, T., Walsh, S. D., Fydrich, T. & Graef-Calliess, I. T. (2023). Impact of new country, discrimination, and acculturation-related factors on depression and anxiety among ex-Soviet Jewish migrants: data from a population-based cross-national comparison study. International Review of Psychiatry, 35(4), 289-301.

United Nations. (1948). Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos. ONU. https://n9.cl/imy

United Nations. (2022). Desafíos Globales: Migración. ONU. https://n9.cl/nkqrc3

United Nations. (2023). Desafíos Globales Migración. Naciones Unidas. https://www.un.org/es/global-issues/migration

Van der Laat, C. (2017). La migración como determinante social de la salud en Cabises, B., Bernales, M. y McIntyre, A. M. (Eds.). La migración internacional como determinante de la salud social en Chile: evidencia y propuesta para políticas públicas (pp.1-520). Chile, Universidad del Desarrollo de Chile.

Vearey, J. (2023). Migration and Health in the WHO-Afro Region: A Scoping Review. African Centre for. Disponible https://migration.org.za/migration-and-health-in-the-who-afro-region-a-scoping-review/ (12 febrero 2023).

Vélez, C., Escobar, M. D. P. y Pico, M. E. (2013). Determinantes sociales de la salud y el trabajo informal. Revista costarricense de salud pública, 22(2), 156-162.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024-1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

World Health Organization. (1946). Constitución de la Organización Mundial de la Salud, firmada en Nueva York el 22 de julio de 1946. OMS. Disponible https://onx.la/57df6. (6 febrero 2023).

World Health Organization. (2019). Promoting the health of refugees and migrants lobal action plan, 2019–2023. WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHA72-2019-REC-1

World Health Organization. (2023). Discapacidad. ONU. Disponible https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health. (1 febrero 2023).