Artículos

Scenarios, trends and differences in entrepreneurship in Southern Spain and Nothern Morocco: a gender perspective

Escenarios, tendencias y diferencias en el emprendimiento en el sur de España y el norte de Marruecos: una perspectiva de género

Scenarios, trends and differences in entrepreneurship in Southern Spain and Nothern Morocco: a gender perspective

Ehquidad: La Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, núm. 18, pp. 83-114, 2022

Asociación Internacional de Ciencias Sociales y Trabajo Social

Recepción: 22 Febrero 2022

Aprobación: 27 Abril 2022

Abstract: Many political and research agendas place the entrepreneurial subject at the epicentre of economic development. Our objective was to use a gender perspective to study asymmetries in the perception of entrepreneurship in two different but close geographic areas: Northern Morocco and Southern Spain. We conducted a survey of 1233 people in Spain and Morocco. In Morocco, the participants were (a) a sample of students from the Abdelmalek Essaadi University in the Tangier-Tetouan area and (b) a sample of university graduates living in the same area. In Spain, the participants were a sample of students from the University of Malaga (Spain). We administered a questionnaire on the participants' perceptions of entrepreneurship opportunities in their setting, their own social and political attitudes toward entrepreneurship, and their self-perception of their own entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. Our results confirm and expand on the trends described in international reports and the scientific literature. They also provide new data that may be of help in meeting the challenge posed by the gender gap in business entrepreneurship.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Gender Gap, Attitudes, Morocco, Spain.

Resumen: Muchas agendas políticas y de investigación sitúan al sujeto emprendedor en el epicentro del desarrollo económico. El objetivo de nuestro estudio consistió en analizar, desde un enfoque de género, las asimetrías en la percepción del emprendimiento empresarial en dos zonas geográficas diferentes pero cercanas: el norte de Marruecos y el sur de España. Realizamos una encuesta a 1233 personas en España y Marruecos. En Marruecos, los y las participantes fueron (a) una muestra de estudiantes de la Universidad Abdelmalek Essaadi en la zona de Tánger-Tetuán y (b) una muestra de egresados/as universitarios/as residentes en la misma zona. En España, la muestra estuvo constituida por estudiantes de la Universidad de Málaga (España). Administramos un cuestionario sobre la percepción de las oportunidades de emprendimiento en su entorno, las actitudes sociales, las políticas de emprendimiento y la autopercepción sobre conocimientos y habilidades empresariales. Nuestros resultados confirman y amplían las tendencias descritas en informes internacionales y en la literatura científica. También se aportan nuevos datos que pueden ser útiles para afrontar el reto que supone la brecha de género en el terreno del emprendimiento empresarial.

Palabras clave: Emprendimiento empresarial, Brecha de género, Actitudes, Marruecos, España.

1. INTRODUCTION: SUBJECTS AND AGENCY IN BUSINESS DYNAMICS

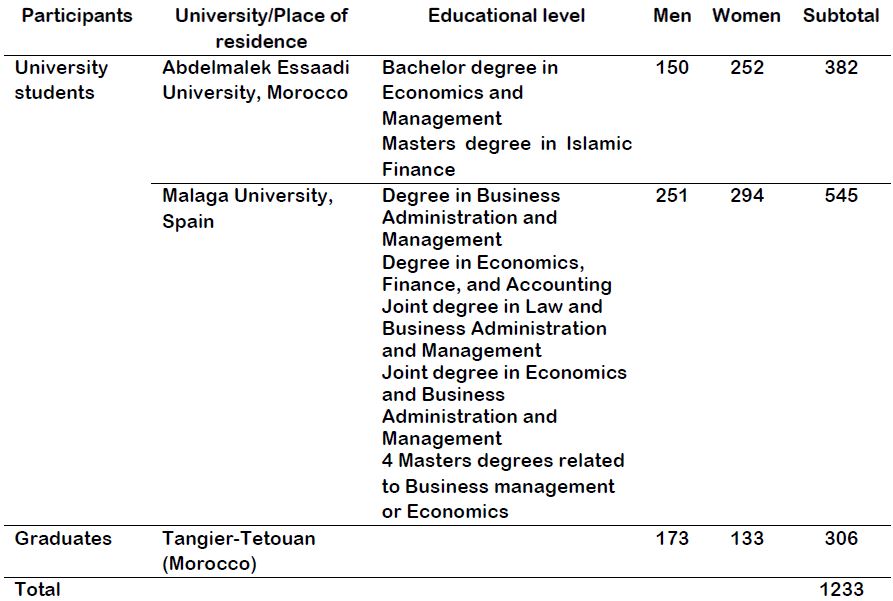

This objective of this study was to investigate the perception of entrepreneurship in the north of Morocco and the south of Spain from a gender perspective. We compared the opinions of male and female graduates from Tangier and Tetouan (Morocco), university students at Abdelmalek Esaadi University (AEU), which is in the same Moroccan region, and Spanish students from the University of Malaga (UMA), Spain. All students were studying degrees related to business management and economics.

Internationalization is one of the fundamental pillars of the strategic plans of the UMA. Thanks to its geographical situation by the Mediterranean Sea, Málaga city is a natural bridge between Europe and Africa, serving as a link between the EU and its neighboring countries, including Morocco. Abdelmalek Essaadi University is expanding its relationships with the EU via an international strategy that includes extensive experience in Erasmus+ and mobility projects.

Although entrepreneurship is a route by which women enter the economy of developing countries, women's skills are not actively sought or encouraged in the setting of entrepreneurship. This situation has been influenced by socio- economic and cultural factors, such as patriarchal and discriminatory attitudes toward women in all areas of life. Patriarchal patterns continue to exert a strong influence on Moroccan and Spanish society and explain the submissive and passive role adopted by many women in these regions. This issue is particularly relevant in the rural areas of northern Morocco, where it is fueled by poverty and the low schooling rates of girls, whose future is envisioned as homemakers and family carers.

This study compared the perception of entrepreneurship in Northern Morocco and Southern Spain. These areas are close in geographic terms, but are distant in their economical, social, and cultural aspects. We compared the opinions of participants with similar levels of education and training to identify the limitations and self-limitations of men and women in their approach to self- employment in their respective environments. This comparative perspective may help to rethink relationships between countries and territories, because it serves to explore a new concept of border that is permeable and bidirectional, not only in the transfer of people or goods, but in life and work expectations.

The interest of this article also lies in its multidisciplinary approach. As authors, we have over 20 years' experience in gender and feminist studies. We suggest that our analysis could play a diagnostic role in helping to highlight the demands of the participants and to develop collaborative networks between women in both areas. This study is the result of the cooperation project "The empowerment of female micro-entrepreneurs in Northern Morocco”, which was funded by the Volunteer Program for International Cooperation in Development (Programa de Voluntariado en Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo) approved by the UMA in 2014.

2. ASYMMETRIC PROFILES AND BARRIERS: AN OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT SITUATION

The ongoing incorporation of women into the business world is having a strong effect on society (Verheul, Uhlaner & Thurik, 2005). However, there are still significantly fewer women than men involved in start-up businesses (Kelley, Bosma & Amorós, 2010; Orlandini, 2018). Henry, Foss & Ahl (2016) suggested that although most research disaggregates data by sex, few studies have used a gender perspective to analyze business entrepreneurship. Women tend to be analytically invisible in national and international studies (Stevenson, 1986; Litz & Folker, 2002). This aspect is mainly due to two factors (Justo, 2008). On the one hand, entrepreneurial analysis generally "normalizes" the traditional male approach to doing business. On the other hand, women start up fewer businesses, and these businesses are considered to have little economic weight.

However, many recent political and research agendas consider the entrepreneurial subject to be the primary and fundamental driver of economic development (Veciana, 2007). Women can no longer be perceived as subjects of little concern because they are undisputable agents of wealth- generating processes (Teti et al., 2020). Research on female entrepreneurship helps in understanding the behavior of women in business settings, human behavior as a whole, and the relationship between human behaviour and employment and social welfare (Bruin, Brush & Welter, 2007; Minniti, 2009).

Although women are essential agents of social change, their economic participation is uneven in different regions of the world. In a developing country like Morocco, objectives that must be addressed include the support and encouragement of female entrepreneurs, promotion of equality at work, improvement in women's socioeconomic conditions, professionalization, defense of women's rights and interests, and the promotion of business and professional associations. Since 1999, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Consortium has been publishing the GEM reports, which investigate entrepreneurship in worldwide economies with a wide range of economic development. They show that in most of the countries investigated an increase in the participation of women can lead to greater and faster growth in new businesses. The data on entrepreneurship show that, in general, there are fewer women than men entrepreneurs, although female incorporation continues to increase with a slow but steady reduction of the gender gap (GEM. Women’s Entrepreneurship 2016/2017 Report, 2017). Of the 49 countries surveyed by the GEM Consortium in 2018, it is worth noting that only six showed similar rates of entrepreneurship between men and women. These six countries were among those generally classified as impoverished or developing: Indonesia, Thailand, Panama, Qatar, Madagascar, and Angola (GEM Global Report, 2018).

There is growing interest among various disciplines in understanding the factors that influence and affect female entrepreneurship (Ortiz, Duque & Camargo, 2008). This new trend has moved the focus of analysis from individual differences to the study of the social determinants that restrict the participation of women and men in business life. Women's attitudes and behaviors in the business setting cannot be analyzed in isolation from the economic and sociocultural environment in which they operate (Rani & Rao, 2007) because social values have a strong influence on the conditions under which women create and develop businesses. Incorporating the gender perspective as an explanatory tool is fundamental to the structural analysis of this situation. The gender approach also highlights the value that women bring to the labour market and the power of women's demands on the development of political agendas (Barbera y Martínez, 2004).

Gender perspectives were gradually incorporated into academic research (Minniti & Naudé, 2010) in the late 1980s, and showed great analytical potential for understanding female entrepreneurship. In the mid-1980s, Bowen and Hisrich (1986) conducted a literature review to identify the main topics addressed by such research up to that point in time and the conclusions they had reached. Their purpose was to determine the variables that influenced female versus male entrepreneurship in order to understand the values, opportunities, and barriers that women encountered. According to Ruiz, Camelo, and Coduras (2012), the general characteristics of female entrepreneurship should be framed within contextual, demographic, and perceptual factors. However, Giménez (2012) suggested that the psychological, sociocultural, and economic domains should be analyzed.

Regarding the psychological perspective, Henríquez, Mosquera, and Arias (2010) proposed that perceptual variables were an essential component in female entrepreneurship. Verheul, Uhlaner, & Thurik (2005) argued that entrepreneurial self-perception had a strong impact on business achievements, while Langowitz and Minniti (2007) concluded that in the business environment, women assessed themselves less favorably than men. Rábago, D’annunzio, and Monserrate (2014) addressed self-efficacy, locus of control, and the need for achievement in Argentine women. Díaz, Hernández, Sanchez, and Postigo (2010) studied female entrepreneurs in Extremadura (Spain) in the period 2003 to 2005. Their main finding was that the perception of good business opportunities and fear of failure were gender-dependent. This finding was in line with the results of the 2017-2018 GEM Consortium Report for Spain. These results showed that women had lower scores than men in relation to perceiving new business opportunities, trusting their skills, and having entrepreneurial role models, but they had higher scores on other variables that inhibit entrepreneurial behavior, such as fear of failure. The present study includes these variables because they can be used to define entrepreneurial attitudes in women in two ways: (a) some variables address how people perceive their environment (i.e. their perceptions of opportunities, and the level of political and institutional support); and (b) other variables focus on people self-perceptions (i.e. their perceived knowledge and experiences, and their fear of failure). We also included the variable acquaintance with other entrepreneurs, which has a strong impact on entrepreneurial intentions (GEM. Women’s Entrepreneurship 2016/2017 Report, 2017).

Directly connected with the foregoing aspects, several studies have investigated female motivation when starting a business. Cromie (1987) analyzed the reasons why men and women started businesses. The results were based on personal interviews and indicated that the wish to earn money was the main differentiator between genders. Women gave less importance to this objective and saw entrepreneurship as a means of simultaneously satisfying their own professional needs and the needs of their children. Following this idea, DeMartino & Barbato (2003) studied motivations based on marital status and the presence of dependent minors in the household. Women greatly valued flexibility and work-family life compatibility, whereas men prioritized income. Having children increased the propensity of women to create their own business. As Gundry and Ben-Yoseph (1998) suggested, sociocultural factors are directly related to women's family commitment. These authors analyzed the impact of culture and family on the strategies, opportunities, and obstacles to the growth of female entrepreneurs in Romania, Poland, and the USA. Mattis (2004) concluded that women probably start up businesses more out of necessity than choice, because as employees they cannot find quality employment that would allow them to fulfill their family responsibilities. González (2011) suggested that entrepreneurship among immigrant women in Spain is driven by a strategy of confronting labor market gender segregation and the desire to gain autonomy and professional independence. In this sense, Verheul, Van Stel, and Thurik (2004) concluded that entrepreneurship provides women with greater life satisfaction than it does to men.

Studies have also addressed the main barriers women face when starting a business and have shed light on the situation of women within business world. Women are not a homogeneous group (Shabbir & Di Gregorio, 1996), and therefore it is not the case that all female entrepreneurs will encounter the same difficulties. Constantinidis, Lebègue, Abboubi & Salman (2019) concluded that ethnicity (Smith-Hunter & Boyd, 2004) or social class modulated the difficulties encountered by Moroccan women. Bouzekraoui & Ferhane (2017) summarized the main problems of female entrepreneurs in Morocco. Their difficulties included financing, market access, acquisition of infrastructure, hiring staff, administrative barriers, work and family life reconciliation, poor training, and the burden of a patriarchal mentality. Basargekar (2007) described the challenges faced by women in India, which can be extrapolated to the global level. Orlandini (2018) summarized such challenges as poor access to credit, inadequate training, little business vision, and conservative social attitudes. The lack of access to public contracts (Loscocco & Robinson, 1991), external financing (Guzman & Kacperczyk, 2019) or access to risk capital (Malmström, Johansson & Wincent, 2017; Alsos & Ljunggren, 2017) also has a strong impact on female entrepreneurship.

Amorós and Pizarro (2008) used the GEM data to analyze the entrepreneurial dynamics of women in a sample of women from Chile. They found that although it is socially accepted in Chile for women to start new businesses, they have fewer opportunities and insufficient incentives to start them. Several studies have highlighted the persistence of stereotypes and gender roles. Gupta, Wieland and Turban (2019) showed that there was still a widespread perception of men and women being associated with high-growth and low-growth entrepreneurship, respectively. Sánchez and Fuentes confirmed the impact of traditional gender stereotypes (Sánchez and Fuentes, 2013). They compared male and female university students regarding their entrepreneurial intentions and their perception of entrepreneurship. They concluded that in the near future female university students could have a greater tendency to create new businesses than men. Bastian, Metcalfe, and Zali (2019) showed that a culture of inequality leads to limited entrepreneurial behaviour in both men and women. Pérez-Quintana and Hormiga (2012) suggested that despite the continued existence of the male entrepreneur stereotype, androgynous stereotypes are also emerging, which is suggestive of a change in how entrepreneurship is conceived.

In a literature review of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), Becerra, Leyva and Pérez (2010) identified the way female entrepreneurs dealt with the challenges faced during the internationalization of their business. For example, women used networking to create competitive advantages. Rodríguez, Moya and Rodríguez (2018) also found that women tended to use social networks and media to develop their businesses. Weeks and Seiler (2001) interviewed Latin American businesswomen on the topic of what they needed to expand their businesses. Their replies were unanimous: access to information and technology, to capital and national and international markets, and to networks such as women's business associations and regional business organizations.

The 2017 GEM Report for the Middle East and North Africa described the obstacles faced by female entrepreneurs with low levels of education and status in their social environment. These obstacles included the lack of female role models, fewer networks within their communities, lack of capital and assets, and last but not least, lack of confidence in their ability to succeed in business. The latter attitude is culturally induced by traditional gender patterns (GEM, 2017; Ennaji, 2020; Louahabi, Moustaghfir, and Cseh, 2020), which is similar to the situation in Spain (Butkouskaya, Romagosa, and Noguera, 2020).

Therefore, given the potential of institutional and social support to increase the number of female entrepreneurs (Baughn, Chua & Neupert, 2006; Brindley, 2005), it is relevant to deepen our understanding of gender- associated problems in order to design constructive policies that may help women to overcome barriers and fulfill their business potential.

All these aspects show that men and women perceive success in different ways. Justo (2008) analyzed the extent to which businesswomen and businessmen differed in the way they perceive and evaluate business success. Family factors, and especially the status of parents, play a key role in shaping the different perceptions of success in women. Clancy (2007) concluded that success often requires full-time commitment to work and a proportional reduction in the time dedicated to families and personal lives. This may be the price that women have to pay, thus making them unable to obtain the same results as their male peers or to define success in a different way. Clancy attributed these two options to personal decisions rather than to the influence of the gender mandate. Eddleston and Powell (2008) investigated business success using a survey of 201 business owners. Women had less economic success than men, but they were more satisfied with their jobs because their concept of success was less related to fluctuations in productivity and sales. These authors also highlighted that women hoped to contribute to society and generate jobs, whereas men wanted to satisfy their status needs. This finding supports the view that gender is a key element in the entrepreneurial mindset.

There are several studies on company size and business style. Regarding size, Guacaneme (1999) found that in Colombia the greatest participation of women was in microenterprises. This finding was similar to that of Weeks and Seiler (2001), who found that in Latin America women owned between a quarter and a third of microenterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises. Research conducted by the USA National Foundation for Women Business Owners (NFWBO) in Latin America and in other regions of the world found that female owners, regardless of their nationality, have many things in common given that their lines of business are similar and they face the same types of problems and challenges in starting and developing their businesses. Eversole (2004) drew attention to the potential of microenterprises run by women to alleviate poverty in their communities, while pointing out that their capacity to fight this was very limited. Brenes and Bermúdez (2013) used the Second National Survey of Microenterprises to study the characteristics of female entrepreneurs and their limitations in Costa Rica. The results showed that female participation in Costa Rican SMEs was very low and was restricted to microenterprises. They found that women encountered major obstacles in areas such as entrepreneurial experience, business knowledge, resources to start an enterprise, and the heavy reliance on business revenues. Huaita and Valenzuela (2004) used data from the CASEN 2000 Socioeconomic Characterization survey to evaluate the impact of women microentrepreneurs in Chile on income generation. Female owners of single- worker businesses tended to have a lower educational level than the rest of the working population: nevertheless, they had greater average income than salaried women. In Venezuela, Carosio (2004) found that different types of microenterprises were run by women depending on their education level, the roles they assumed, and their needs. Regarding business styles, Buttner (2001) used focus groups to analyze the relational roles used by female entrepreneurs. Women's entrepreneurial style tended to be democratic and participatory, to encourage team building, and to promote collaborative decision-making.

This brief review of the literature shows that there is growing interest in understanding the factors that influence and determine female entrepreneurship, particularly in relation to the creation, development, and maintenance of new businesses. It also draws attention to the need to investigate women's motivations, their world views, career paths, and need for self-realization, as well as their attitudes and behavior in relation to successful companies, their problems, and policies that help or hinder business start-up by women. In summary, it is relevant to investigate the areas that make up the life projects of entrepreneurial women by studying their social and economic opportunities.

3. METHODS AND PROCEDURES

This study compared gender-based perceptions of entrepreneurship in Northern Morocco and Southern Spain to address the knowledge gap regarding these geographical areas. This descriptive study measured the gender distribution of replies to questions on entrepreneurship administered to three different populations at a specific point in time. This study serves as a first approach to future research of greater analytical depth.

The study hypotheses were as follows: (a) there are gender differences in the perceptions of entrepreneurship in the geographical areas studied; and (b) socioeconomic and psychosocial aspects underlie any such differences. The overall objective of the study was to identify the gender-based elements that encourage or discourage entrepreneurship.

We constructed and administered a questionnaire to Moroccan students from AEU in the Tangier-Tetouan region, and to Spanish students from the UMA. All students were studying degrees related to business management. The sample was selected by random sampling stratified by type of degree and academic year. The questionnaire was also administered to a sample of the general population from the Tangier-Tetouan region who already had graduated with a university degree. The field work was completed in 2019.

own work

The questionnaire underwent initial testing to ensure the accuracy of the questions. In Morocco, it was administered by teaching faculty members who had been specifically trained on-site by two of the authoresses of this article. The questionnaire addressed the following issues: the participants' perceptions of the entrepreneurial environment in their area, and the participants' self-perceptions of their own entrepreneurial capabilities and skills.

The questionnaire was prepared by the authors of this article, taking as a reference the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor reports mentioned at the beginning of this article. The work of other authors was also taken into account (Veciana y Urbano, 2004); Veciana, Aponte & Urbano, 2005; Sánchez, Díaz, Hernández y Postigo, 2011; Owusu-Ansah, 2012; De Jorge, 2013; Paço, Ferreira, Raposo, Rodrigues & Dinis, 2013; Marques, Ferreira, Gomes & Rodrigues, 2013). The guidelines provided by Fuentes and Sánchez were followed to include the gender perspective in the framework of entrepreneurship (Fuentes y Sánchez, 2010; Díaz, Hernández, Sánchez y Postigo, 2010; y Giménez, 2012).

The questionnaire was organized into three main blocks. The first block included a battery of questions on the environment (i.e. the perception of opportunities for entrepreneurship, relationship with other entrepreneurs, and intention to start a new business). The second block contained questions on the participants' perceived level of knowledge, skills, and experience to create a business and on the value they attached to fear of failure as a limiting factor in entrepreneurship. Both types of questions were closed, the only possible answers being "yes", "no", and "don't know/did not reply". The third block included a battery of items on a Likert scale to obtain opinions on public policies in favor of female entrepreneurship, the levels of perceived equality when starting a business, and the social vision of female entrepreneurship.

4. RESULTS: ANALYSIS OF GENDER, PERCEPTION OF BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES, AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Table 2 shows that in all three groups women perceived fewer opportunities for entrepreneurship than men. The responses to the question "Do you think that in the next 6 months there will be good opportunities to start a new business in the area where you live?" showed that confidence in the existence of opportunities was higher among both Moroccan groups than among the Spanish participants. Pessimism was higher among the UMA university students and even higher in the UMA female subgroup.

| Yes | 55.5 % (96) | 65.3 % (113) | 56.6 % (98) | |

| Male | No | 22.5 % (39) | 19.7 % (34) | 19.7 % (34) |

| 173 | Don’t know/No | 22.0 % (38) | 15.0 % (26) | 23.7 % (41) |

| reply | ||||

| Yes | 50.4 % (67) | 54.9 % (73) | 48.9 % (65) | |

| Female | No | 29.3 % (39) | 36.1 % (48) | 20.3 % (27) |

| 133 | Don’t know/No | 20.3 % (27) | 9.0 % (12) | 30.8 % (41) |

| reply | ||||

| Participants from Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Morocco | ||||

| Yes | 43.0 % (56) | 37.7 % (49) | 31.5 % (41) | |

| Male | No | 28.5 % (37) | 50.8 % (66) | 62.3 % (81) |

| 130 | Don’t know/No | 28.5 % (37) | 11.5 % (15) | 6.2 % (8) |

| reply | ||||

| Yes | 34.5% (87) | 32.9 % (83) | 23.4% (59) | |

| Female | No | 23.4% (59) | 49.6% (125) | 70.6% (178) |

| 252 | Don’t know/No | 42.1% (106) | 17.5% (44) | 6.0% (15) |

| reply | ||||

| Participants from Malaga University, Spain | ||||

| Yes | 22.3 % (56) | 54.6% (137) | 25.5% (64) | |

| Male | No | 37.1 % (93) | 37.8% (95) | 44.6% (112) |

| 251 | Don’t know/No | 40.6% (102) | 7.6% (19) | 29.9% (75) |

| reply | ||||

| Yes | 18.4% (54) | 52.4% (154) | 19.4% (57) | |

| Female | No | 41.8% (123) | 42.2% (124) | 53.1% (156) |

| 294 | Don’t know/No | 39.8% (117) | 5.4% (16) | 62.3 % (81) |

| reply | ||||

Regarding perceived entrepreneurship opportunities, the lowest gender gap (4%) was among UMA students and the highest gender gap was among AEU students (8.5%).

Regarding the question “Do you know someone who had started a business in the last 2 years”, the highest percentage of positive responses was given by the group of Moroccan male graduates (65.3%), followed by their female peers (54.9%). This result was expected since this group had more possibilities of being exposed to the job market. However, in relation to this aspect, the percentage of Moroccan female graduates (54.9%) and UMA male students (54.6%) were very similar.

Moroccan AEU students had the least contact with new entrepreneurs in their area. The number of UMA male students who knew some entrepreneurs was 17% higher than that of their male counterparts from the AEU, whereas the number of UMA female students who knew some new entrepreneurs was 19.5% higher than that of their AEU female counterparts.

Compared to their male counterparts, all the women in each of the three groups knew fewer entrepreneurs: the lowest difference by gender was found among the UMA students (2.2%). This result was similar to that concerning the first question. Compared to their female counterparts, the number of male students who knew someone who was starting a business was 4.8% higher. This gender difference increased to 10.4% between male and female graduates. This percentage was almost five times higher than that of the Spanish students.

Regarding entrepreneurial intentions, ("Are you thinking of starting a new business or company, either alone or with partners, in the next 3 years, including any form of self-employment?"), the results show that in all groups women were less likely than men to start up their own business. These results were similar to those related to the previous questions. The highest percentage of participants intending to start a new business was found among Moroccan graduates (56.6% men and 48.9% women). This percentage was closely followed by those of male students from the AEU and the UMA. The groups that were least inclined to start a new business were AEU female students (23.4%, a percentage similar to that of UMA male students) and UMA female students (19.4%).

The greatest differences by gender were again found among Moroccan students (8.1%), followed by Moroccan graduates (7.7%). The difference between UMA male and female students was 6.1%.

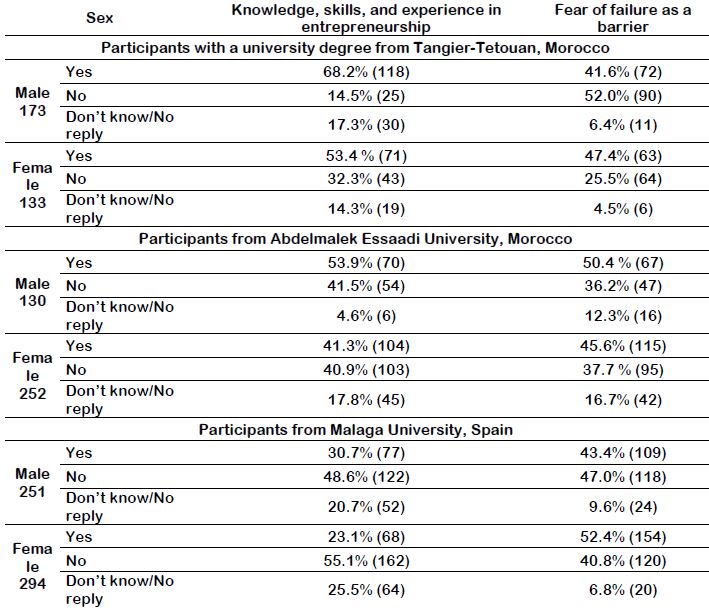

Table 3 shows the results on the participants' self-perceptions of their capabilities, skills, and experience of entrepreneurship, and whether they thought fear of failure was a barrier to entrepreneurship. Overall, we found that gender was a strong mediator in the entrepreneurial phenomenon.

Table 3. Self-perception of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, Skills, And Experience, and Fear of Failure as a Barrier

own work

Table 3 shows that women reported having less confidence than men in relation to the question "Do you have the knowledge, skills, and experience required to start up a business?". This result is similar to that shown in Table 2, which showed significant differences by gender in perceived business opportunities in their area and in entrepreneurial intentions. However, the gender gap is greater in relation to self-perceptions of skills and experience. Across all groups, women perceived themselves as being less capable than the men in their group. They did not trust their skills, were less self-confident, and had less confidence in their training. Regarding their entrepreneurship skills, there was a 12.6% difference between the male and female Moroccan students and a 14.8% difference between the male and female participants in the group of Moroccan graduates. Once again, the gap was smaller among the UMA male students.

Some other results on male and female perceptions are of releUvance. Moroccan male graduates had the highest levels of confidence, and almost 70% of them felt they were capable of running a business. This was the highest percentage found in the survey. Next in rank were AEU male students, closely followed by Moroccan female graduates; in both cases, over 53% of the participants stated that they felt confident with their entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. The difference between Moroccan female graduates and AEU female students was practically the same as the difference between AEU male and female students. On the other hand, although 41.3% of the AEU female students felt confident with their entrepreneurial knowledge and skills, seven times more women than men gave a "Don't know" response or "No response" to the item on the self-evaluation of their skills and knowledge.

The Spanish students had the lowest levels of confidence and the female students were even less confident than their male counterparts. There was an 18% difference between the female students from the two universities, and the Moroccan female students had higher levels of confidence in their knowledge and skills.

Regarding the question "Would fear of failure be a barrier to starting a new business?", there was a clear difference between Moroccan female graduates and their male counterparts: fear of failure was reported by 47.4% of the women and by 41.6% of the men. A similar difference was found between the UMA male and female students. However, AEU female students did not follow this pattern: fear of failure was reported by 45.6% of the female students and by 51.5% of the male students. The differences by gender within each group do not follow the previous pattern. The greatest difference was found between UMA male and female students (9%). However, there was little difference by gender between the AEU students and the general population with a university degree (5.9% and 5.8%, respectively).

In summary, the highest levels of fear of failure as an obstacle were found among Spanish female students and Moroccan male students (52.4% and 51.1%, respectively). Furthermore, fear of failure was 6.8% higher among Spanish female students than among Moroccan female students. This finding may be explained by the possibility that Moroccan female students feel less pressure to succeed because traditional gender models do not require them to be successful at work.

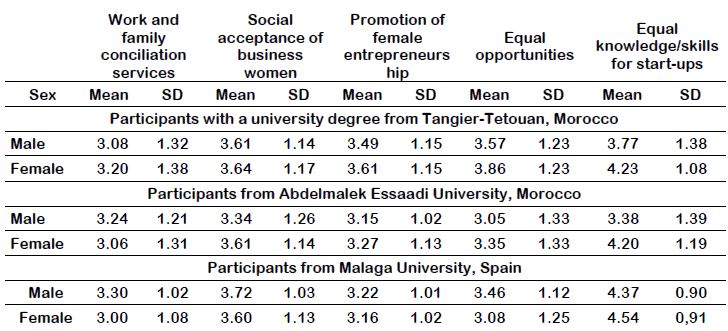

own work

Table 4 shows the participants’ opinions on public policies in support of female entrepreneurship. Regardless of their university of origin, more male than female students supported the view that sufficient social services were available such that women could continue to work after having a family. However, lower dispersion in the set of scores from the UMA male students suggests that their opinion was more evenly distributed than that of the AEU male students. However, female students did not offer a strong opinion on this issue. The perception that life-work conciliation services were sufficient was stronger among Moroccan female graduates, whereas their male counterparts had little or no opinion on this issue.

Nevertheless, all the participants agreed that "The creation of a company is a socially accepted professional option for women." Moroccan male students had the lowest score on this item, but it appears that they change their opinion once they have finished their university studies and have entered the labour market. UMA male students strongly agreed that business women are well accepted by society: their opinion showed little statistical variability.

Regarding the statement that "Self-employment or the creation of business is promoted among women", agreement was stronger among Moroccan graduates of both genders than among Spanish and Moroccan students. More Moroccan female graduates than their male counterparts stated that self- employment was encouraged in their area. However, more UMA male students than their female counterparts stated that this was the case.

Far more Moroccan female graduates than their male counterparts agreed with the statement that "women and men have equal access to good opportunities to create a company ". More AEU female students than their male counterparts also agreed with this statement: however, the AEU male students did not express a clear opinion on this issue. In contrast, whereas Spanish male students thought that both genders have equal opportunities for entrepreneurship, their female counterparts did not share their view.

All Spanish UMA students agreed with the statement that "Women have the same level of knowledge and skills as men to set up a business": this statement was associated with the lowest standard deviation (see Table 4). It is noteworthy that although Spanish female students thought that their own entrepreneurial knowledge and skills were low, they strongly supported the statement on gender equality in knowledge and skills. In both groups of Moroccan participants, women gave the strongest support to the statement on entrepreneurial equality between men and women. There was less agreement with this statement among men in both Moroccan groups; in fact, AEU male students agreed the least with this statement.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In any socio-economic growth strategy, cultivating an entrepreneurial spirit among young people must be a core objective. Likewise, a high priority in any political agenda must be the promotion of equal opportunities and female empowerment. Being a woman continues to be a risk factor for poverty, and until equal opportunities are achieved, the entrepreneurial talent of more than half of the world's population remains invisible.

We would like to emphasize that the policies aimed at sustainable human development need to take into account the dignity and self-esteem of all citizens. This aim will not be achieved if women continue to be absent from decision-making settings, that is, settings in which power is exercised. This view has been supported in different international documents and, specifically, in the Master Plans for Spanish Cooperation since 2005.

We found that female participants generally perceived fewer opportunities in their settings and knew fewer entrepreneurs; therefore, they are less likely to start a business than their male counterparts. Indeed, UMA female students were the most pessimistic group regarding entrepreneurial opportunities. In absolute terms, AEU female students also knew fewer entrepreneurs. As other studies have suggested, this result could be due to the fact that women have fewer female business role models. For example, the 2017 GEM Consortium Middle East and North Africa Report pointed out that one of the main barriers faced by women entrepreneurs is that they lack female business role models and are thus hindered from accessing networks within their communities. Nevertheless, compared to male and female university students in Tangier-Tetouan, Moroccan female graduates know more entrepreneurs in the same area. However, these women know fewer entrepreneurs than their male counterparts.

Similar to the results reported by Sánchez and Fuentes (2013), we found that female university participants were the least likely group to start a business in the next 3 years and of these groups AEU female students were the least likely to do so. In relation to starting a business, we suggest that the variables that have the greatest negative impact on female students are the lack of female business role models and the scarcity of business networks.

In support of this suggestion, the results show that in each group men were more confident than women regarding their knowledge, skills, and experience in starting new businesses. There was a large difference in the level of confidence expressed regarding knowledge, skills, and experience: Moroccan male graduates had more self-confidence in their capabilities (68.2%), whereas Spanish female students had the least self-confidence (23.1%). Moroccan female graduates and AEU male students had very similar levels of confidence, suggesting that although the AEU male students had yet to complete their studies, they felt as capable as the female graduates.

In relation to starting a new business, Moroccan male graduates were the group least affected by fear of failure, whereas UMA female students were the most affected group. In line with the results reported in the literature (see Introduction), in general, women were more afraid of failure than their male counterparts. However, AEU female students were less afraid of failure than their male counterparts. This difference may be explained by the fact than in a traditional gender culture, women are under less pressure than men to be successful in their jobs.

In relation to all the items of the questionnaire, the smallest gender differences were found between UMA students. The only exception was related to the item on fear of failure: more UMA female students than male students were afraid of failure. This difference was the highest among the three groups under study. Nevertheless, the fact that the smallest gender differences were found between UMA students may suggest that traditional gender models have less of an impact on Spanish students than on Moroccan participants. Advances in equal access to the labor market may entail that both men and women are exposed to similar pressures.

Regarding issues related to the institutional and social promotion of business start-ups, male students, regardless of their university, thought that sufficient family-work reconciliation services were available to women. However, more female Moroccan graduates than their male counterparts thought that there were sufficient services. Similar results were also found in relation to the promotion of female entrepreneurship. More AEU female students than their male counterparts thought that progress was being made in this regard: however, UMA female students were less optimistic on this issue than their male counterparts. By contrast, in relation to the social acceptance of business women, UMA female students believed that setting-up their own business was a good professional option for them.

Regarding perceived access to equal opportunities, Moroccan women were more confident than men, regardless of whether they were graduates or still at university. They also thought that they had the same opportunities as their male counterparts to start up a business and that they had same level of knowledge and skills as the men in their setting. UMA students of both genders thought that their level of knowledge and skills was similar. However, the female students did not think that their business opportunities were the same as those of their male peers. Although UMA female students gave the worst evaluation of their own capabilities to set up a business (Table 3), they were confident about female capabilities in general (Ahmed, Chandran, Klobas, Liñán, & Kokkalis, 2020).

This study contributes to the continuing debate on gender asymmetries in business dynamics by comparing perceptions of entrepreneurship in two geographic areas, which to date have received little attention in this regard. We suggest that it is relevant to provide evidence in support of policies that promote entrepreneurial activity in the areas under study. Richer and more cohesive societies can only be developed if the barriers associated with gender discrimination are deeply understood and confronted.

In 2015, the UN approved the Sustainable Development Goals to address the global challenges agenda until 2030. They identified 17 goals: the 5th goal is to promote gender equality and women's autonomy. Research has shown that there has been an increase in women's contribution to entrepreneurship in the majority of developed countries. This increase is effectively promoting equality and making citizens co-responsible for their own development. However, the present study highlights the need for agendas for change in these countries in order to continue encouraging social advances in gender equality. This aspect is of particular relevance when the process of globalization is blurring current models, showing that much remains to be done to achieve an economic development model that is inclusive and sustainable for women. In Northern Morocco and in Malaga, more women than men are immersed in situations of poverty and social exclusion.

The present analysis could contribute to theoretical and practical advances by providing empirical evidence that may encourage theoretical reflection on entrepreneurship from a feminist and gender perspective. The scarcity of studies using a feminist interpretive framework has led to a knowledge gap that may be hindering the future evolution of successful entrepreneurship. Applying a gender approach may help to deepen our knowledge of the facets and obstacles men and women encounter in the setting of entrepreneurship. This approach is needed to investigate the phenomenon in its entirety and complexity. This study shows that traditional stereotypes and mentalities continue to operate in the two study areas. The female groups seem to be more homogenous and share some patterns other than their economic, political, social, and cultural differences. It was found that the gender characteristics of potential entrepreneurs are quite similar in both countries and that the gender gap continues to exist. This kind of evidence is fundamental to obtaining a more inclusive vision of entrepreneurship such that it becomes a lever of egalitarian development at many levels in the societies in which this is taking place. The comparative analysis provides information on two areas that are geographically close, but socioculturally, politically, and economically different. This study could serve to guide other studies on similarities and differences in bordering countries. The analysis could also serve as a basis to design practical proposals, such as the creation of collaboration networks and communication tools for women in both areas. The latter proposals are among our immediate objectives.

We would like to point out some limitations of the study that may guide future lines of research. The student sample should be larger and other groups in Morocco and Spain should be studied. The sociodemographic variables used could be increased. The descriptive analysis could have been enhanced by the application of a qualitative approach, which would involve the implementation of data collection techniques such as in-depth interviews or focus-group discussions. The use of these qualitative techniques could deepen our knowledge of the phenomenon. We plan to conduct a qualitative analysis in a second phase of the study. Because this study is cross-sectional, a longitudinal study would be relevant to monitor the evolution of entrepreneurship in these areas. In any case, the preliminary data obtained in this study serves as a starting point for future research. It should be noted that we analyzed two countries that necessarily have to cooperate to achieve higher levels of wealth and human development in order to increase wellbeing in both areas.

6. REFERENCES

Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., Klobas, J. E., Liñán, F., & Kokkalis, P. (2020). How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100327; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100327

Alsos, G.A. & Ljunggren, E. (2017). The role of gender in entrepreneur– investor relationships: A signaling theory approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(4), 567-590.

Amorós, J.E. & Pizarro, O. (2008). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Mujeres y Actividad Emprendedora Chile 2007-2008. Santiago de Chile: Universidad del Desarrollo.

Barbera, E. y Martínez, I. (Coords.) (2004). Psicología y Género. Madrid: Pearson, Prentice- Hall.

Basargekar, P. (2007). Women entrepreneurs: Challenges faced. The ICFAI Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 4(4), 6-15.

Bastian, B.L., Metcalfe, B.D., & Zali, M.R. (2019). Gender Inequality: Entrepreneurship Development in the MENA Region. Sustainability, 11, 6472; https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226472

Baughn, C., Chua, B., & Neupert, K. (2006). The Normative Context for Women's Participation in Entrepreneruship: A Multicountry Study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 687-708; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00142.x

Becerra, S., Leyva, S., y Pérez, K. (2010). PYMES desde una perspectiva de género: Las mujeres como líderes de la internacionalización de los negocios a través de la creación de redes. Available online: http://www.konradlorenz.edu.co/images/publicaciones/suma_negocios_w orking_papers/2011-v1-n1/05-mujeres-lideres-internacionalizacion.pdf

Bouzekraoui, H. & Ferhane, D. (2017). An exploratory study of women’s entrepreneurship in Morocco. Journal of Entrepreneurship: Research & Practice, Vol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.5171/2017.869458

Bowen, D. & Hisrich, R. (1986). The Female Entrepreneur: A Career Development Perspective. Academy of Management Review, 11(2), 393- 407; https://doi.org/10.2307/258468

Brenes, L. y Bermúdez, L. (2013). Diferencias por género en el emprendimiento empresarial costarricense. Tec Empresarial, 7(2), 19-27; https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v7i2.1510

Brindley, C. (2005). Barriers to women achieving their entrepreneurial potential: Women and risk. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11(2), 144-161; https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510590554

Bruin, A., Brush, C., & Welter, F. (2007). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women's entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 323–339.

Butkouskaya, V., Romagosa, F., y Noguera, M. (2020). Obstacles to Sustainable Entrepreneurship Amongst Tourism Students. Sustainability, 12(5), 1812; https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051812

Buttner, E.H. (2001). Examining female entrepreneurs' management style: An application of a relational frame. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 253- 269.

Carosio, A. (2004). Las mujeres y la opción emprendedora: consideraciones sobre la gestión. Revista Venezolana de Estudios de la Mujer, 9(23), 79- 112.

Clancy, S. (2007). ¿Por qué no hay más mujeres en la cima de la escala corporativa: debido a estereotipos, a diferencias biológicas o a escogencias personales? Academia, Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 38, 1-8.

Constantinidis, C., Lebègue, T., El Abboubi, M., & Salman, N. (2019). How families shape women’s entrepreneurial success in Morocco: an intersectional study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1786-1808; https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0501

Cromie, S. (1987). Similarities and Differences between Women and Men Business. Proprietorship. International Small Business Journal, 5(3), 43- 60; https://doi.org/10.1177/026624268700500304

De Jorge, J. (2013). Análisis de los factores que influyen en la intención emprendedora de los estudiantes universitarios. Aracciolos, 1(1), 1-12.

DeMartino, R. & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 815-832.

Díaz, J. C., Hernández, R., Sánchez, M. C., y Postigo, M. V. (2010). Actividad emprendedora y género. Un estudio comparativo. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 19(2), 83-89.

Eddleston, K. & Powell, G. (2008). The paradox of the contented female business owner. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 24-36; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.12.005

Ennaji, M. (2020). Women’s Activism in North Africa: A Historical and Socio- Political Approach. In Double-Edged Politics on Women’s Rights in the MENA Region, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 157-178.

Eversole, R. (2004). Change Makers? Women's Microenterprises in a Bolivian City. Gender, Work & Organization, 11(2), 123-142; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00225.x

Fuentes, F. y Sánchez, S. M. (2010). Análisis del perfil emprendedor: una perspectiva de género. Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 28(3), 1-28.

GEM. Informe GEM España 2017-2018 (2018). Available online: http://www.gem-spain.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Informe-GEM- 2017-18.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2020).

GEM. 2017/2018 Global Report (2018). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2017-2018-global-report (accessed on 12 February 2020).

GEM. Middle East and North Africa Report (2017). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2017-middle-east-and-north- africa-report (accessed on 10 February 2020).

GEM. Women’s Entrepreneurship 2016/2017 Report (2017). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20162017-womens- entrepreneurship-report (accessed on 11 February 2020).

Giménez, D. (2012). Factores DS del emprendimiento femenino: Una revisión bibliográfica. Revista venezolana de estudios de la mujer, 17(38), 127-142

González, N. (2011) Migrantes, procesos de irregularización y lógicas de acumulación y exclusión. Un estudio desde la filosofía política (tesis doctoral). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Guacaneme, M. (1999). La mujer microempresaria de la microempresa: la experiencia colombiana. Available online: http://library.fes.de/fulltext/iez/01111toc.htm

Gundry, L. & Ben-Yoseph, M. (1998). Entrepreneurs in Romania, Poland, and the United States: Cultural and Family Influences on Strategy and Growth. Family Business Review, 11(1), 61-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741- 6248.1998.00061.x

Gupta, V.K., Wieland, A.M., & Turban, D.B. (2019). Gender characterizations in entrepreneurship: A multi‐level investigation of sex‐role stereotypes about high‐growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 131-153.

Guzman, J. & Kacperczyk, A. O. (2019). Gender gap in entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 48(7), 1666-1680

Henríquez, M. C., Mosquera, C., y Arias, A. (2010). La creación de empresas en Colombia desde las percepciones femenina y masculina. Economía Gestión y Desarrollo, 10, 61-77.

Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal, 34(3), 217-241.

Huaita, F. y Valenzuela, P. (2004). Ingresos y microempresarias en Chile. Available:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Patricio_Valenzuela2/publi cation/23746830_Ingresos_y_Microempresarias_en_Chile/links/004635231 d3e75c820000000.pdf

Justo, R. (2008) La influencia del género y entorno familiar en el éxito y fracaso de las iniciativas emprendedoras (tesis doctoral). Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Kelley, D., Bosma, N., & Amorós, J.E. (2010). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2010, Executive Report. Available online: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/228073 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

Langowitz, N. & Minniti, M. (2007). The Entrepreneurial Propensity of Women. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(3), 341-364.

Loscocco, K. & Robinson, J. (1991). Barriers to women’s small-business success in the United States. Gender and Society, 5(4), 511-532.

Louahabi, Y., Moustaghfir, K., & Cseh, M. (2020). Testing Hofstede’s 6-D model in the North and Northwest regions of Morocco. Human Systems Management, 39(1), 105-115.

Litz, R. & Folker, C. (2002). When he and she sell seashells: Exploring the relationship between management team gender-balance and small firm performance. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(4), 341-359.

Malmström, M., Johansson, J., & Wincent, J. (2017). Gender stereotypes and venture support decisions: how governmental venture capitalists socially construct entrepreneurs’ potential. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(5), 833-860.

Marques, C., Ferreira, J., Gomes, D., & Rodrigues, R. (2013). Entrepreneurship Education: How Psychological, Demographic and Behavioural Factors Predict the Entrepreneurial Intention. Education & Training, 54(8/9), 657-672.

Mattis, M. (2004). Women entrepreneurs: out from under the glass ceiling. Women in Management Review, 19 (3), 154-163; https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420410529861

Minniti, M. (2009). Gender issues in entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 5(7–8), 497–621.

Minniti, M. & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? European Journal of Development Research, 22, 277-293.

Orlandini, I. (2018). Emprendimientos femeninos indígenas y capital social. Revista Investigación & Negocios, 17, 6-12.

Ortiz, C., Duque, Y., y Camargo, D. (2008). Una revisión a la investigación en emprendimiento femenino. Revista Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, XVI(1), 85-104.

Owusu-Ansah, W. (2012). Entrepreneurship Education, a Panacea to Graduate Unemployment in Ghana? International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(15), 211-220.

Paço, A., Ferreira, J., Raposo, M., Rodrigues, R., & Dinis, A. (2013). Entrepreneurial Intentions: Is Education Enough? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 1-20; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0280-5

Pérez-Quintana, A. y Hormiga, E. (2012). La influencia de los estereotipos de género en la orientación emprendedora individual y la intención de emprender. Investigación y género, inseparables en el presente y en el futuro. En I. Vázquez Bermúdez (coord.), Actas del IV Congreso Universitario Nacional Investigación y Género, Sevilla, 1527-1553.

Rábago, P., D’Annunzio, MC., y Monserrate, S. (2014). El Perfil de las Mujeres emprendedoras exitosas. Available online: http://www.icesi.edu.co/ciela/anteriores/Papers/emjg/3.pdf

Rani, S. & Rao, S. (2007). Perspectives on women Entrepreneurship. The ICFAI Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 4(4), 18-27.

Rodríguez, R., Moya, P.J., y Rodríguez, E. (2018). El papel de las redes sociales en el emprendimiento femenino. Un avance en el contexto español. Available online: https://seville2019.econworld.org/papers/Rodriguez_fernandez_vidales_T heRole.pdf

Ruiz, J., Camelo, M. C., y Coduras, A. (2012). Actividad emprendedora de las mujeres en España. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer.

Sánchez, M. C., Díaz, J. C., Hernández, R., & Postigo, M. V. (2011). Perceptions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship. An analysis of gender among university students. International Entrepreneurship Management Journal, 7, 443–446.

Sánchez, S. y Fuentes, F. (2013). Gender and entrepreneurship: analysis of a young university population. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 13(1), 65-78.

Shabbir, A. & Di Gregorio, S. (1996). An examination of the relationship between women’s personal goals and structural factors influencing their decisión to star a business: The case of Pakistan. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(6), 507-529.

Smith-Hunter, A. & Boyd, R. (2004). Applying theories of the relationship between women’s personal goals and structural factors influencing their decision to start a business: The case of Pakistan. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 507–529.

Stevenson, M.K. (1986). A discounting model for decisions with delayed positive and negative outcomes. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 115, 131-154.

Teti, A., Abbott, P., Talbot, V., & Maggiolini, P. (2020). Gender Equality in Theory and Practice. In Democratisation against Democracy. Palgrave Macmillan, 247-289.

Veciana, J.M. (2007). Entrepreneurship as a scientific research programme. En Cuervo, A; Ribeiro, D.; Roig, S. (Eds.), Entrepreneurship. Concepts, Theory and Perspective (23-71) Berlin: Springer.

Veciana, J. M. y Urbano, D. (2004). Actitudes de los estudiantes universitarios hacia la creación de empresas: un estudio empírico comparativo entre Catalunya y Puerto Rico. El emprendedor innovador y la creación de empresas de I+ D+ I, Universidad de Valencia, pp. 35-58. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=aIWzyLD4PUEC&oi=fnd&pg= PA35&dq=VECIANA+Y+URBANO&ots=kjC1PZKt5_&sig=RI9YnmL8Nimrzr7 ZccA6AXhhk_8#v=onepage&q=VECIANA%20Y%20URBANO&f=false

Veciana, J. M., Aponte, M. & Urbano, D. (2005) University student’s attitudes towards entrepreneurship: A two countries comparison. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(2), 165–182.

Verheul, I., Uhlaner, L., & Thurik, R. (2005). Bussiness accomplishments, gender and entrepreneurial self-image. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(4), 483-518.

Verheul, I., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, R. (2004). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship across 29 countries. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18, 1-32.

Weeks, J. & Seiler, D. (2001). Actividad empresarial de la mujer en América Latina. Una exploración del conocimiento actual. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo Washington, D. C., Serie de informes técnicos del Departamento de Desarrollo Sostenible.